Pacific Madrone TheHeath Family– Ericaceae

(ar-BYOO-tus men-ZEE-zee-eye)

Names: The Pacific Madrone is the only common broadleaved evergreen tree in our region. It is known by many names. In the northwest it is more familiarly called Madrona, whereas in California it is more often called Madrone or sometimes Coast Madrono (Madrono is Spanish for Strawberry tree). British Columbians simply call it Arbutus. In fact there is a song, Arbutus Baby, about a Madrona seedling by the children’s musician “Raffi.” My son was excited to be able to explain to his classmates what an Arbutus was when his teacher played this song in his second grade class!

Relationships: There are over 1,500 species of plants in ericaceae, including blueberries, huckleberries, cranberries, rhododendrons, heathers and salal. All members have tubular flowers (usually four or five petals that are fused at the base). Almost all grow in acid soils and depend on fungal mycorrrhiza for efficient uptake of water and nutrients. Two other species of Arbutus found in the U.S. and Mexico are the Texas Madrone (A. texana) and the Arizona Madrone (A. arizonica). More familiar to gardeners is the Strawberry Tree, Arbutus unedo, which is native to the Mediterranean.

Relationships: There are over 1,500 species of plants in ericaceae, including blueberries, huckleberries, cranberries, rhododendrons, heathers and salal. All members have tubular flowers (usually four or five petals that are fused at the base). Almost all grow in acid soils and depend on fungal mycorrrhiza for efficient uptake of water and nutrients. Two other species of Arbutus found in the U.S. and Mexico are the Texas Madrone (A. texana) and the Arizona Madrone (A. arizonica). More familiar to gardeners is the Strawberry Tree, Arbutus unedo, which is native to the Mediterranean.

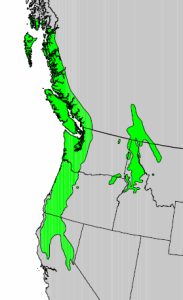

Distribution: Pacific Madrone is found along the pacific coast from southern British Columbia to San Diego County in California.

Growth: Pacific Madrone is the largest member of ericaceae, sometimes reaching 100 feet (34m) tall; usually 30 to 75 feet (10-25m). One well-known tree on Cherry Street in Port Angeles, Washington has a circumference of over 20 feet (7m). Madrones may live 250 years or more (some estimate that it may live 400-500 years). Whereas conifers show extreme apical dominance– where the top growing point relies on gravity to transport hormones that ensure it will grow with a straight trunk, Madrones, in contrast, are extremely phototropic, meaning that the top growing points will seek the sun. In fact, when growing in the sun, Madrones tend to be more bush-like. It is when they are growing in competition with other trees they grow taller, often leaning to seek out brightest spot.

Growth: Pacific Madrone is the largest member of ericaceae, sometimes reaching 100 feet (34m) tall; usually 30 to 75 feet (10-25m). One well-known tree on Cherry Street in Port Angeles, Washington has a circumference of over 20 feet (7m). Madrones may live 250 years or more (some estimate that it may live 400-500 years). Whereas conifers show extreme apical dominance– where the top growing point relies on gravity to transport hormones that ensure it will grow with a straight trunk, Madrones, in contrast, are extremely phototropic, meaning that the top growing points will seek the sun. In fact, when growing in the sun, Madrones tend to be more bush-like. It is when they are growing in competition with other trees they grow taller, often leaning to seek out brightest spot.

Habitat: In our area Madrones are most often found on dry, sunny sites, often on bluffs above the seashore with a south or west exposure. In the southern part of its range in California, it is found in moister valleys.

Diagnostic Characters: Pacific Madrone is easy to recognize by its leathery, oval-shaped leaves. Old leaves are shed in the summer. Also in summer, especially where exposed to the sun, the cinnamon-colored bark peels off to reveal smooth, light green, younger bark that turns golden with age. Older Madrones, growing in a forest, retain a scaly, reddish brown bark. White, urn-shaped flowers, in large drooping clusters, make an appearance in spring, followed by orange-red berries with a bumpy or granular surface in autumn.

In the landscape, Madrone gets mixed reviews. Many people love their attractive peeling bark, evergreen leaves, and showy flowers and fruit. Other people bemoan their messy nature, the fact that they drop leaves and bark throughout the summer. For this reason, Madrones should not be planted next to a patio or in a lawn. Another reason Madrones should not be planted in an irrigated lawn is because it susceptible to a root rot, Phytophthora cactorum. Madrones also do not respond well to disturbance. When tall, skinny Madrones that were once growing in a forest, are exposed to the sun, their bark begins to peel. These, thin-barked trees are much more susceptible to the canker disease, Nattrassia mangiferae. Pruning cuts may also provide easy access to the pathogen. Leaf spots that are caused by many different fungi also can make a Madrone unsightly. Sometimes leaves will turn totally brown, but will recover when new leaves are produced in the spring. If this has been a problem, old leaves should be raked up and destroyed to limit reinfection. Despite all its problems, Madrone is a worthy tree. It can prove its magnificence if it is planted in a west or south-facing exposure, rarely irrigated, and left to its own devices.

Phenology: Bloom Period: Mid-March-June. Berries ripen mid-September to mid-November; seeds are dispersed by birds and rodents, but will also just drop to the ground.

Propagation: Seeds need to be separated from the berry, then given a cold-moist stratification at 40ºF (4ºC) for 60 days– or plant them outside in fall for natural stratification.

Use by people: The wood can be made into attractive veneer, furniture and hardwood floors. The wood varies in color from very light to a dark purple. It makes excellent firewood. The berries are edible but were rarely eaten by natives.

Use by Wildlife: The berries are an important food for pigeons, doves, thrushes and robins. Wood rats will also eat the fruit and deer will eat the foliage. Madrone is also a preferred tree species for cavity-nesting birds, especially woodpeckers, nuthatches, and wrens. Songbirds, small owls and mammals such as raccoons, porcupines and squirrels will move in to cavities abandoned by woodpeckers. As with all members of ericaceae, the flowers attract pollinators such as bees and hummingbirds.

Note: For my master’s thesis I studied the Possible Causes of Decline for the Pacific Madrone (Arbutus menziesii) (1995). and presented my findings at the Proceedings of the April 28, 1995 Symposium: “The Decline of Pacific Madrone (Arbutus menziesii Pursh): Current Theory and Research Directions.”

Links:

Consortium of Pacific Northwest Herbaria

WTU Herbarium Image Collection, Plants of Washington, Burke Museum

E-Flora BC, Electronic Atlas of the Flora of British Columbia

Jepson Manual, University of California

Ladybird Johnson Wildflower Center

USDA Forest Service-Fire Effects Information System

Native Plants Network, Propagation Protocol Database

Native American Ethnobotany, University of Michigan, Dearborn