Giant Chain Fern Chain Fern family–Blechnaceae

Woodwardia fimbriata Sm.

(Wood-WAR-dee-uh fim-bree-AH-tuh)

Photo Courtesy of Claudia Riedener

Names: The genus is named after British botanist Thomas J. Woodward. Chain Ferns get their common name from the chain-like rows of oblong sori on the undersides of the pinnae. The species name, fimbriata means fringed, due to the margins having many tiny spines. This species may also be called Western Chain Fern or Giant Chain Ferry.

Relationships: There are about 14-20 species of Woodwardia in the northern hemisphere, with only 3 species in the U.S. and Canada.

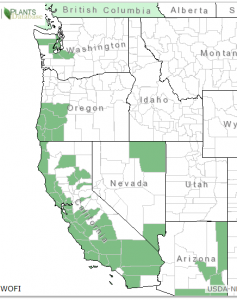

Distribution of Giant Chain Fern from USDA Plants Database

.

.

.

Distribution: Giant Chain Fern has been found in Texada and Vancouver Islands in British Columbia, and in the Puget Sound region of Washington where it is listed as sensitive. It is more common from southern Oregon and California to northwest Mexico, mostly near the coast, but can also be found inland in Arizona and Nevada.

Growth: Fronds typically grow 1-5 feet (0.4-1.5 m) but may grow up to 9 feet (3m).

Habitat: Giant Chain Fern grows in mild, wet coastal forests. It is sometimes found growing on seepy coastal cliffs or in desert areas near shady seeps. Wetland designation: FACW, it usually occurs in wetlands, but is occasionally found in non-wetlands.

Photo Courtesy of Claudia Riedener

Diagnostic Characters: Evergreen fronds grow upright or slightly bent, from a short, robust rhizome. They are broadly feather-shaped with once-pinnate, deeply cut segments; margins having pointed teeth tipped with tiny spines.

In the Landscape: About Woodwardia fimbriata, Hitchcock writes: “This is surely our choicest large fern.” Being the largest, it is certainly the most impressive of all our ferns, it performs best in a woodland garden especially next to streams, bogs, springs or ponds, but it can also grow in full sun with adequate summer moisture. It can be very striking as a focal point or when planted against a wall in a shady location. It readily produces “sporeling plants” in wet areas. It also may be propagated in the spring by division of the rhizomes–but judicious collection of spores is preferable where this species is rare.

Use by People: Natives in California used the leaves for fiber to make baskets, and to line the top and bottom of an earth oven for baking acorn bread and other foods.

Links:

Consortium of Pacific Northwest Herbaria

WTU Herbarium Image Collection, Plants of Washington, Burke Museum

E-Flora BC, Electronic Atlas of the Flora of British Columbia

Jepson Eflora, University of California

Ladybird Johnson Wildflower Center

Native American Ethnobotany, University of Michigan, Dearborn