Willows The Willow Family– Salicaceae

Salix sp.

Relationships: There are more than 300 species of willow worldwide, mostly in the northern hemisphere. Hitchcock and Cronquist describe 38 species in Vascular Plants of the Pacific Northwest. Exact identification of these trees and shrubs is extremely difficult. Vegetative characters are variable even on the same plant. Even technical floral characteristics may have some variability, making it difficult even for experts to determine the exact species. Add to that, willows will often hybridize naturally in the wild, creating another level of complexity. In the landscape, they all play a similar role, so it may not make much difference if the willow you plant in your landscape was misidentified.

Habitat: Willows generally grow along streams where the soil is moist. They grow quickly and are very useful for controlling erosion along waterways.

Diagnostic Characters: Many willows form attractive catkins known as “pussy willows.” Branches brought inside may be forced to bloom in late winter. Because the pussies, or catkins lengthen as the flowers mature, many pictures you see will not show the tight “pussy” that many people would recognize.

Phenology: Bloom Period: Catkins often appear before or with the leaves beginning in February. Although willows are mostly insect pollinated, pollen is also carried by the winds and is another major allergen–dispersed mostly in March. Tiny insects, as in the above photo, can often be found on willow catkins. I think you would need an entomologist to identify them all! The small, silky seeds of willows ripen quickly and are scattered by the wind in April.

Propagation is easy. You can stick a branch in the ground and it will form roots and continue to grow. Living fences can be created with willow posts, (as long as the posts are buried right side up!) Seeds may germinate within 12-24 hours of dispersal. The seeds contain chlorophyll and are ready to photosynthesize—all they need is moisture and light! “Volunteers” weeded out of other areas can be easily potted up or transplanted to more appropriate locations.

Use by People: Natives used the bark of willows for making string. Willow branches are good basket-making material. Not surprisingly the bark was also used medicinally. Willow bark contains salicin, the chemical from which aspirin (ASA) was first synthesized.

Use by Wildlife: Willows provide food and cover for many wildlife species. A preferred food of moose, willow leaves and bark are also consumed by deer and beaver. Willow catkins produce nectar that attracts bees and other pollinators. The following species are the ones most commonly found in the nursery trade:

(SAY-licks hook-er-ee-ANN-uh)

Hooker’s willow is often called Dune Willow, Beach Willow or Coastal Willow. It has also been known as S. piperi and S. amplifolia. A large shrub or small tree, to 18 feet (6m), it has attractive pussies in early spring before the leaves appear. Its stout twigs and 1.5-5” (4-12cm) long, oval to egg-shaped leaves are very hairy when young. As its common names suggest it is sometimes found on sandy beaches. Wetland designation: FACW-, Facultative-wetlands, it occurs more often in wetland than non-wetland. Blooms: March-April.

Hooker’s willow is often called Dune Willow, Beach Willow or Coastal Willow. It has also been known as S. piperi and S. amplifolia. A large shrub or small tree, to 18 feet (6m), it has attractive pussies in early spring before the leaves appear. Its stout twigs and 1.5-5” (4-12cm) long, oval to egg-shaped leaves are very hairy when young. As its common names suggest it is sometimes found on sandy beaches. Wetland designation: FACW-, Facultative-wetlands, it occurs more often in wetland than non-wetland. Blooms: March-April.

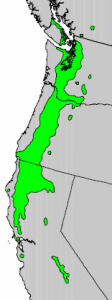

Distribution of Hookers Willow from USGS ( “Atlas of United States Trees” by Elbert L. Little, Jr. )

Links:

Consortium of Pacific Northwest Herbaria

WTU Herbarium Image Collection, Plants of Washington, Burke Museum

E-Flora BC, Electronic Atlas of the Flora of British Columbia

Jepson Manual, University of California

Ladybird Johnson Wildflower Center

Native American Ethnobotany, University of Michigan, Dearborn

(SAY-licks LOO-sid-uh subspecies la-see-ANN-druh)

Pacific Willow (also known as S. lasiandra) may also be known as Shining (the meaning of lucida) Willow, Western Black Willow, Yellow Willow, or Gland Willow. Lasiandra means “wooly stamens.” It is one of our largest native willows, reaching 20-60 feet (6-18m). It is the easiest to identify because of its lance-shaped leaves, 2-6 inches (5-15 cm) long. Its smooth branches are attractive in winter, especially in varieties that have yellow twigs. Wetland designation: FACW+, Facultative wetland, it usually occurs in wetlands, but sometimes occurs in non-wetlands. Blooms: March-June.

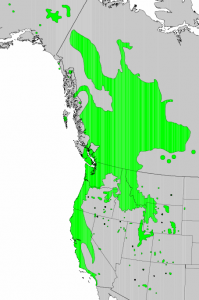

Distribution of Pacific Willow from USGS ( “Atlas of United States Trees” by Elbert L. Little, Jr. )

Links:

Consortium of Pacific Northwest Herbaria

WTU Herbarium Image Collection, Plants of Washington, Burke Museum

E-Flora BC, Electronic Atlas of the Flora of British Columbia

Jepson Manual, University of California

Ladybird Johnson Wildflower Center

USDA Forest Service-Fire Effects Information System

Native Plants Network, Propagation Protocol Database

Native American Ethnobotany, University of Michigan, Dearborn

(SAY-licks scow-lair-ee-ANN-uh)

Scouler’s Willow is also known as Upland Willow, due to its ability to thrive in drier habitats. It is a small multi-stemmed tree or shrub, growing 6-36 feet (2-12m). Its leaves are smaller than some of the other willows, only 1-3 inches (3-8cm), rounded or pointed at the tip, widest above the middle, tapering to a narrow base. It rapidly invades disturbed sites; some may consider it too weedy for the more domesticated landscape. Wetland designation: FAC, facultative, it is equally likely to occur in wetland or non-wetlands. Blooms: March-June.

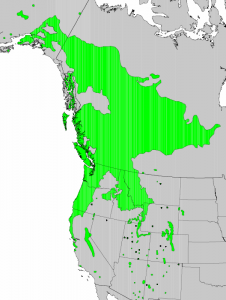

Distribution of Scoulers Willow from USGS ( “Atlas of United States Trees” by Elbert L. Little, Jr. )

Links:

Consortium of Pacific Northwest Herbaria

WTU Herbarium Image Collection, Plants of Washington, Burke Museum

E-Flora BC, Electronic Atlas of the Flora of British Columbia

Jepson Manual, University of California

Ladybird Johnson Wildflower Center

USDA Forest Service-Fire Effects Information System

Native Plants Network, Propagation Protocol Database

Native American Ethnobotany, University of Michigan, Dearborn

National Register of Big Trees

- Sitka Willow Salix sitchensis Sanson ex Bong.

Sitka Willow is also a pussy willow; each pussy has a brown bract, which makes an attractive contrast against the silvery, furry inflorescence. It grows 3-24 feet (1-8m) tall. The leaves are slightly larger (1.5 to 3.5 inches, 4-9cm) than Scouler’s Willow but similarly shaped. The undersides of the leaves have satiny, short, soft hairs. Wetland designation: FACW, it usually occurs in wetlands but occasionally is found in non-wetlands. Blooms: April-June.

Sitka Willow is also a pussy willow; each pussy has a brown bract, which makes an attractive contrast against the silvery, furry inflorescence. It grows 3-24 feet (1-8m) tall. The leaves are slightly larger (1.5 to 3.5 inches, 4-9cm) than Scouler’s Willow but similarly shaped. The undersides of the leaves have satiny, short, soft hairs. Wetland designation: FACW, it usually occurs in wetlands but occasionally is found in non-wetlands. Blooms: April-June.

Links:

Consortium of Pacific Northwest Herbaria

WTU Herbarium Image Collection, Plants of Washington, Burke Museum

E-Flora BC, Electronic Atlas of the Flora of British Columbia

Jepson Manual, University of California

Ladybird Johnson Wildflower Center

Native American Ethnobotany, University of Michigan, Dearborn

Other willows that may be found in the Pacific Northwest:

| Common Name | Scientific Name | Blooms | Size | Wetland |

| Barclay’s Willow | S. barclayi | Jun-Aug | 1-3m | FACW |

| Undergreen Willow | S. commutata | Jun-Sep | 1-3m | OBL |

| Geyer’s Willow | S. geyeriana | Apr-Jun | 1.5-5m | |

| Bog Willow | S. pedicelllaris | Apr-Jun | 0.4-1.5m | OBL |

| Diamondleaf Willow | S. planifolia = S. phylicifolia | May-Jul | 0.2-4m | OBL |

| Mackenzie’s Willow | S.prolixa= Salix rigida var. mackenzieana | Apr-Jun | 1-5m |

Some alpine willows may be appropriate for rock gardens. These low-growing shrubs or groundcovers usually have attractive upright catkins. Most are less than 20 inches (50cm) tall. Examples include: Arctic Willow, Salix arctica, Snow Willow, S. nivalis, and Cascade Willow, S. cascadensis.