Paper Birch The Birch Family–Betulaceae

Betula papyrifera Marsh.

(BET-yoo-la pap-er-IH-fur-uh)

Name: Paper Birch gets its name from the way the bark on older trees will peel in thin, white, papery sheets. It is also sometimes called Canoe Birch or White Birch.

Relationships: There are about 40 species of Birch trees in the northern temperate regions of the world, about 15 in North America.

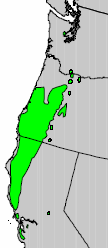

Distribution of Paper Birch from USGS ( “Atlas of United States Trees” by Elbert L. Little, Jr. )

Distribution: Paper Birch is widely distributed throughout the northern regions of North America from Alaska to Newfoundland. It is common in the Great Lakes region and northeastern United States. In the western U.S. it is mostly found in eastern Washington, northern Idaho and western Montana. West of the Cascades, Paper Birch is mostly found north of the Skagit in Washington State, but may also occur in the southern Puget Sound region.

Growth: Paper Birch grows quickly to about 90 ft (30m). It is short-lived, rarely living longer than 125-200 years.

Habitat: It grows best in moist sites, in open woods.

Wetland designation: FAC, Facultative, it is equally likely to occur in wetlands or non-wetlands.

The white bark peels in papery sheets.

Diagnostic Characters: Although the white, papery bark is a good identification character for older trees, young, darker barked trees may be confused with Bitter Cherry. Both have horizontal lines of lenticels on the bark. The leaves of Paper Birch are sharply pointed; the margins are doubly toothed. Paper Birches produce catkins that appear before or at the same time as the leaves. The catkins break up at maturity

In the landscape: Paper Birches are best planted in groves, creating a woodland effect that especially highlights their distinctive white trunks. It is best, however, to avoid planting birches next to where cars will be parked because the resident insect population may drip sticky honeydew throughout the summer!

Phenology: Bloom Period: Mid-April to early June. Birch pollen is also a major allergen. Small winged nutlets ripen early August to mid-September. Most are disseminated by the wind from September to November.

Propagation: Paper Birch is easily propagated by seed, stratified at 40ºF (4ºC) for 90 days. After treatment, sown seeds should be exposed to light at least 8 hours a day.

Use by People: Paper Birch, as its other name suggests, was used, especially by eastern natives, for canoes. It also was also frequently used for making baskets. The wood is commonly used for furniture, cabinets, plywood, and pulp and paper products, as well as firewood. Paper Birch sap is tapped and made into syrup, wine, beer and medicinal tonics.

Use by Wildlife: Paper Birch is an important moose browse; deer also eat the leaves. Hare, porcupines and beavers eat the bark and young saplings. Birds, such as finches and chickadees, and small rodents, such as voles and shrews, eat Paper Birch seeds. Grouse eat the catkins and buds. Hummingbirds and squirrels may feed at sapwells created by sapsuckers. Many cavity-nesting birds find homes in Paper Birch trees.

Shrubbier birches that may be encountered in the Pacific Northwest include: Resin Birch, B. glandulosa, Dwarf Birch, B. nana, Water Birch, B. occidentalis, and Bog Birch, B. pumila. Water Birch is often used in ornamental landscapes.

Links:

USDA Plants Database

Natural Resources Canada

Consortium of Pacific Northwest Herbaria

WTU Herbarium Image Collection, Plants of Washington, Burke Museum

E-Flora BC, Electronic Atlas of the Flora of British Columbia

Calphotos

Ladybird Johnson Wildflower Center

USDA Forest Service-Fire Effects Information System

Silvics of North America

Virginia Tech ID Fact Sheet + Landowner Fact Sheet

Native Plants Network, Propagation Protocol Database

Plants for a Future Database

Native American Ethnobotany, University of Michigan, Dearborn

National Register of Big Trees