Hairy Honeysuckle

Lonicera hispidula (Lindl.) Douglas ex Torr. & A. Gray

(Lon-IH-sir-ruh hisp-ih-DOO-luh)

Names: Hairy Honeysuckle is also called Pink Honeysuckle or California (Pink or Hairy) Honeysuckle. Hispidula means covered with bristly hairs. The common name, honeysuckle, comes from the fact that children enjoy sucking nectar from the base of the flowers for a sweet treat. The name Lonicera is derived from Adamus Lonicerus (Adam Lonitzer), a German botanist, author of the herbal, Kräuterbuch (1557).

Names: Hairy Honeysuckle is also called Pink Honeysuckle or California (Pink or Hairy) Honeysuckle. Hispidula means covered with bristly hairs. The common name, honeysuckle, comes from the fact that children enjoy sucking nectar from the base of the flowers for a sweet treat. The name Lonicera is derived from Adamus Lonicerus (Adam Lonitzer), a German botanist, author of the herbal, Kräuterbuch (1557).

Relationships: Plants in the genus, Lonicera, are often twining vines but many are arching shrubs. There are about 180 species in the Northern Hemisphere, with about 100 from China, ~20 from North America, and the rest from Europe or North Africa.

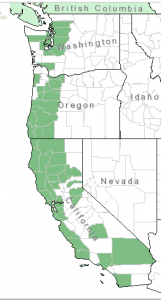

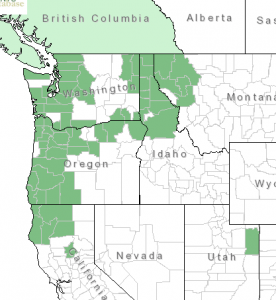

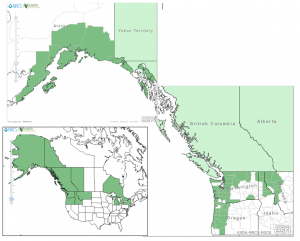

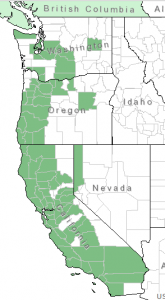

Distribution of Hairy Honeysuckle from USDA Plants Database

Distribution: Hairy Honeysuckle is native from Vancouver Island, in British Columbia to southern California; on the west side of the Cascades in Washington and Oregon; in the Sierras and coastal mountains of California.

Growth: More often a sprawling, shrubby vine, it may also climb up to 3-18 feet (1-6m).

Habitat: It grows in open forests, on drier south, or west slopes, but often grows in coastal riparian areas in California.

Diagnostic Characters: Opposite leaves are variously hairy, sometimes smooth; with the terminal pair joined to form a disc. Pink (or yellow tinged with pink), tubular flowers are born in terminal clusters, accompanied by a pair of axillary clusters. The flowers are two-lipped with the lips about as long as the tube; curling back as the flowers open. Fruits are bright red berries. Stems are hollow.

In the Landscape: Hairy Honeysuckle can be used as a ground cover on a dry slope or may be trained on a trellis. Its attractive, pink flowers are another hummingbird favorite, so it is also a good choice for a wildlife garden.

Phenology: Bloom time: June-August; Fruit ripens: September.

Propagation: Sow seeds as soon as they are ripe in a cold frame or stratify for 90 days at 40º (4º C). Cuttings root easily; they are best taken of half-ripe wood in July or August or mature wood in November.

Use by people: Natives in California used the hollow stems for pipe stems and the burned wood ashes for tattooing.

Use by Wildlife: The flowers provide nectar for hummingbirds. The berries are eaten by grouse, pheasants, flickers, robins, thrushes, bluebirds, waxwings, grosbeaks, finches, and juncos. Small birds may make nests within the twining branches.

Links:

Consortium of Pacific Northwest Herbaria

WTU Herbarium Image Collection, Plants of Washington, Burke Museum

E-Flora BC, Electronic Atlas of the Flora of British Columbia

Jepson Eflora, University of California

Ladybird Johnson Wildflower Center

USDA Forest Service-Fire Effects Information System

Native Plants Network, Propagation Protocol Database

Native American Ethnobotany, University of Michigan, Dearborn

Names: Honeysuckles have long been a garden favorite, grown mostly for their sweetly-scented, nectar-producing flowers. The common name, honeysuckle, comes from the fact that children enjoy sucking nectar from the base of the flowers for a sweet treat. This species is also known as Orange Honeysuckle, Northwest Honeysuckle, or Western Trumpet. The name Lonicera is derived from Adamus Lonicerus (Adam Lonitzer), a German botanist, author of the herbal, Kräuterbuch (1557). Ciliosa, which means having small, fringe-like hairs like eyelashes, refers to the hairy edges of the leaves.

Names: Honeysuckles have long been a garden favorite, grown mostly for their sweetly-scented, nectar-producing flowers. The common name, honeysuckle, comes from the fact that children enjoy sucking nectar from the base of the flowers for a sweet treat. This species is also known as Orange Honeysuckle, Northwest Honeysuckle, or Western Trumpet. The name Lonicera is derived from Adamus Lonicerus (Adam Lonitzer), a German botanist, author of the herbal, Kräuterbuch (1557). Ciliosa, which means having small, fringe-like hairs like eyelashes, refers to the hairy edges of the leaves.

Names: The genus name, Oplopanax, is derived from hoplon, meaning weapon and panakos meaning panacea or “all-heal”—referring to the medicinal qualities of these shrubs and their relationship to the well-known Asian herb, Ginseng, Panax ginseng. Oplopanax is sometimes misspelled, Ophlopanax. Both the common name and specific epithet, horridus, refer to its spiny, wicked-looking appearance. Scientific synonyms include: Echinopanax horridum or horridus, Fatsia horridum, Panax horridum, and Ricinophyllum horridum.

Names: The genus name, Oplopanax, is derived from hoplon, meaning weapon and panakos meaning panacea or “all-heal”—referring to the medicinal qualities of these shrubs and their relationship to the well-known Asian herb, Ginseng, Panax ginseng. Oplopanax is sometimes misspelled, Ophlopanax. Both the common name and specific epithet, horridus, refer to its spiny, wicked-looking appearance. Scientific synonyms include: Echinopanax horridum or horridus, Fatsia horridum, Panax horridum, and Ricinophyllum horridum.

Phenology: Bloom time: May-July; Fruit ripens: June-August, persisting over winter.

Phenology: Bloom time: May-July; Fruit ripens: June-August, persisting over winter.

Names: Pacific Poison-Oak belongs to a genus of plants well known to cause severe skin irritation after contact. Toxicodendron means “poison tree.” Diversilobum means “different lobes,” due to its irregularly lobed leaflets that resemble oak leaves. This species may also be called Western or California Poison-Oak or Yeara.

Names: Pacific Poison-Oak belongs to a genus of plants well known to cause severe skin irritation after contact. Toxicodendron means “poison tree.” Diversilobum means “different lobes,” due to its irregularly lobed leaflets that resemble oak leaves. This species may also be called Western or California Poison-Oak or Yeara.

Growth: Pacific Poison-Oak is usually a shrub growing 3-6 feet (1-2m) tall, but sometimes is a vine growing up to 45 feet (15m). As a vine, a Poison-oak climbs trees or other supports by adventitious roots or by wedging stems within crevices.

Growth: Pacific Poison-Oak is usually a shrub growing 3-6 feet (1-2m) tall, but sometimes is a vine growing up to 45 feet (15m). As a vine, a Poison-oak climbs trees or other supports by adventitious roots or by wedging stems within crevices.

Phenology: Bloom time: April-June; Fruit ripens: August

Phenology: Bloom time: April-June; Fruit ripens: August