Common Snowberry Caprifoliaceae-the Honeysuckle Family

Symphoricarpos albus (L.) S.F. Blake

(sim-for-ih-CAR-poes AL-bus)

Names: Symphori- means “bear together;” –carpos means fruits– referring to the clustered fruits. Albus meaning white, and the common name, Snowberry also refers to the white fruits. This species is sometimes known as Waxberry, White Coralberry, or White, Thin-leaved, or Few-flowered Snowberry.

Names: Symphori- means “bear together;” –carpos means fruits– referring to the clustered fruits. Albus meaning white, and the common name, Snowberry also refers to the white fruits. This species is sometimes known as Waxberry, White Coralberry, or White, Thin-leaved, or Few-flowered Snowberry.

Relationships: The genus Symphoricarpos has about 15 species, mostly native to North and Central America, with one from western China; 12 are found in the United States. Western Snowberry, S. occidentalis, and Mountain Snowberry, S. oreophilis, are mostly found on the east side of the Cascades. Trailing Snowberry, S. hesperius will be discussed in the groundcover section. S. albus var. laevigatus (meaning smooth) is the most common phase found on the Pacific slopes and is more aggressive than the eastern form; it has also been known as S. rivularis or S. racemosa var. laevigatus. It is more aggressive and differs from the S. albus var. albus by being larger, with larger berries and less hairy twigs and leaves. It often escapes cultivation in the eastern United States, and has naturalized in parts of Britain.

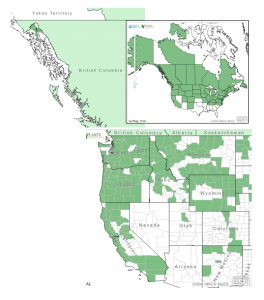

Distribution of Common Snowberry from USDA Plants Database

Distribution: Common Snowberry is found from southeast Alaska to southern California; all across the northern United States and the Canadian provinces.

Growth: This species usually grows 3-9 feet (1-2m) tall.

Growth: This species usually grows 3-9 feet (1-2m) tall.

Habitat: It is found in in dry to moist open forests, clearings, and rocky slopes. It is very adaptable to different conditions. Wetland designation: FACU, it usually occurs in non-wetlands but occasionally is found in wetlands.

Diagnostic Characters: Oval leaves are opposite with smooth or wavy-toothed margins; sometimes hairy on the undersides; often larger and irregularly lobed on sterile shoots. Flowers are small, pink to white bells in dense, few-flowered clusters. Fruit are white berry-like drupes containing two nutlets.

Leaves can be entire or lobed.

In the Landscape: Common Snowberry has long been grown as an ornamental shrub. Winter is its most conspicuous season, where its white berries stand out against leafless branches. Its dainty pinkish flowers are also attractive. Common Snowberry spreads by root suckers and is best given plenty of space to create a wild thicket. It tolerates poor soil and neglect. It is great for controlling erosion on slopes, riparian plantings, for restoration and mine reclamation projects. It is also popular in Rain Gardens.

Phenology: Bloom time: May-August; Fruit ripens: September-October, persisting through winter.

Phenology: Bloom time: May-August; Fruit ripens: September-October, persisting through winter.

Propagation: Stratify seeds warm for 90 days, then stratify for 180 days at 40º (4º C), or sow as soon as seeds are ripe in a cold frame. Cuttings of half-ripe wood may be taken in July or August or of mature wood in winter. Suckers may be divided in the dormant season. Plants resprout from rhizomes after a fire.

Use by People: Snowberries are high in saponins, which are poorly absorbed by the body. Although they are largely considered poisonous, (given names like ‘corpse berry’ or ‘snake’s berry’), some tribes ate them fresh or dried them for later consumption. The berries were used as a shampoo to clean hair. Crushed berries were also rubbed on the skin to treat burns, warts, rashes and sores; and rubbed in armpits as an antiperspirant. Various parts were infused and used as an eyewash for sore eyes. A tea made from the roots was used for stomach disorders; a tea made from the twigs was used for fevers. Branches were tied together to make brooms. Bird arrows were also made from the stems.

Use by Wildlife: Saponins are much more toxic to some animals, such as fish; hunting tribes sometimes put large quantities of snowberries in streams or lakes to stupefy or kill fish. “The Green River tribe say that when these berries are plentiful, there will be many dog salmon, for the white berry is the eye of the dog salmon.” Common snowberry is an important browse for deer, antelope, and Bighorn Sheep; use by elk and moose varies. The berries are an important food for grouse, grosbeaks, robins and thrushes. Bears also eat the fruit. The shrub provides good cover and nesting sites for gamebirds, rabbits, and other small animals. Pocket gophers burrow underneath it. The pink flowers attract hummingbirds, but are mostly pollinated by bees. The leaves are eaten by the Sphinx Moth larvae.

Links:

Consortium of Pacific Northwest Herbaria

WTU Herbarium Image Collection, Plants of Washington, Burke Museum

E-Flora BC, Electronic Atlas of the Flora of British Columbia

Jepson Eflora, University of California

Ladybird Johnson Wildflower Center

USDA Forest Service-Fire Effects Information System

Native Plants Network, Propagation Protocol Database

Native American Ethnobotany, University of Michigan, Dearborn

Names: Black Twinberry is also known as Involucred, Bracted, Bearberry, Fly or Fourline Honeysuckle; or Coast Twinberry. Involucrata refers to the involucres, or bracts that surround the flowers and fruit. Twinberry refers to the 2 berries surrounded by the bracts.

Names: Black Twinberry is also known as Involucred, Bracted, Bearberry, Fly or Fourline Honeysuckle; or Coast Twinberry. Involucrata refers to the involucres, or bracts that surround the flowers and fruit. Twinberry refers to the 2 berries surrounded by the bracts.

Diagnostic Characters: Black Twinberry has opposite leaves that are broadly lance-shaped. It has paired, tubular, yellow flowers arising from the leaf axils. The flowers are 5-lobed, surrounded by large, green or purple bracts. Fruits are shiny, black “twin” berries surrounded by purplish-red bracts. Young, green twigs are 4-angled in cross-section.

Diagnostic Characters: Black Twinberry has opposite leaves that are broadly lance-shaped. It has paired, tubular, yellow flowers arising from the leaf axils. The flowers are 5-lobed, surrounded by large, green or purple bracts. Fruits are shiny, black “twin” berries surrounded by purplish-red bracts. Young, green twigs are 4-angled in cross-section. In the Landscape: It is an attractive shrub and should be used more in the garden. It is a great “edge” species when planted between a forest and more open area. It can be used in a hedgerow or in a Rain Garden. Its fresh, green leaves are similar to Indian Plum; and its dainty, yellow flowers and colorful bracts add interest throughout spring, summer, and fall. Black Twinberry is great for reclamation plantings on riparian sites, in wet meadows and in forests.

In the Landscape: It is an attractive shrub and should be used more in the garden. It is a great “edge” species when planted between a forest and more open area. It can be used in a hedgerow or in a Rain Garden. Its fresh, green leaves are similar to Indian Plum; and its dainty, yellow flowers and colorful bracts add interest throughout spring, summer, and fall. Black Twinberry is great for reclamation plantings on riparian sites, in wet meadows and in forests.

Red Twinberry

Red Twinberry