Names: The Mountain Hemlock, as the name suggests, occurs in the mountains up to the timberline and in subalpine parkland. Hemlock trees are sometimes called “Hemlock Spruces” to differentiate them from the herbaceous Poison Hemlock, which is in the Parsley Family. The name “Tsuga” comes from Japanese words meaning “mother” and “tree.” The species is named after German botanist, Franz Karl Mertens.

Names: The Mountain Hemlock, as the name suggests, occurs in the mountains up to the timberline and in subalpine parkland. Hemlock trees are sometimes called “Hemlock Spruces” to differentiate them from the herbaceous Poison Hemlock, which is in the Parsley Family. The name “Tsuga” comes from Japanese words meaning “mother” and “tree.” The species is named after German botanist, Franz Karl Mertens.

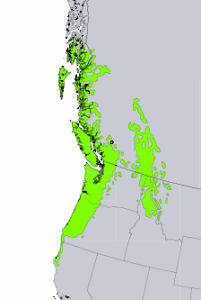

Distribution of Mountain Hemlock from USGS ( “Atlas of United States Trees” by Elbert L. Little, Jr. )

Distribution: Mountain Hemlock is native along the coast of southeastern Alaska and British Columbia, the mountains of Washington and Oregon to the High Sierras of California. It is also found in the Rockies of northern Idaho and Montana.

Growth: In its native habitat, Mountain Hemlock grows very slowly due to the long winters. Subalpine dwarfs may only reach 10 feet (3m). It grows more quickly in lowland areas, typically up to 100 feet (30m). The tallest trees are over 175 feet (50m). The oldest are known to be over 500 years old but some may be over 1000 years old.

Habitat: In the northern part of its range (British Columbia and Alaska), Mountain Hemlock is associated with bogs, and wet areas. It is adapted to deep snow and long winters. It can grow at near freezing temperatures and is can withstand many months covered in snow. The trunks are so flexible that trees bend under the weight of the snow, creating interesting shapes in the snow reminiscent of shepherd’s crooks, snails and embryos. The trees spring upright again after the snow melts. It is less shade tolerant than Western Hemlock.

Wetland designation: FACU, Facultative upland, it usually occurs in non-wetlands.

Diagnostic Characters: Mountain Hemlock can be distinguished from Western Hemlock by the following characters: The leader droops only slightly; the needles are of equal length and are arranged radially around its twigs; and the cones are larger (1-5 inches or 2.5-12.5cm). The branches also tend to sweep upward at the tips.

Bright green lichen grows on the trunks of Mountain Hemlocks above the snow line in Crater Lake National Park.

In the Landscape: Some consider the Mountain Hemlock to be the best native conifer for a small garden. It can be used as a specimen tree in a container or to create a focal point in a rock garden. It creates a picturesque scene when planted in clumps or drifts. Lowland gardeners may be disappointed, however, if they expect their Mountain Hemlock to have the same appearance as the stunted, twisted dwarfs in subalpine meadows.

Phenology: Bloom Period: Mid-May to Mid July. Cones ripen and open from late September to November.

Propagation: Mountain Hemlock can be grown using fresh seed, stratified at 40ºF (4ºC) for 90 days. Vegetative propagation, cuttings and layering, is possible using the same methods as for Western Hemlock.

Use by People: Mountain Hemlock is not used much commercially because of its inaccessibility in high altitudes, but where it is used; it is generally marketed with and used the same as Western Hemlock.

Use by Wildlife: Squirrels make caches of the cones in the snow. Blue Grouse eat the buds and leaves.

Links:

Consortium of Pacific Northwest Herbaria

WTU Herbarium Image Collection, Plants of Washington, Burke Museum

E-Flora BC, Electronic Atlas of the Flora of British Columbia

Jepson Eflora, University of California

Ladybird Johnson Wildflower Center

USDA Forest Service-Fire Effects Information System

Native Plants Network, Propagation Protocol Database

Native American Ethnobotany, University of Michigan, Dearborn