Western Sword Fern The Wood Fern Family–Dryopteridaceae

Polystichum munitum (Kaulf.) C. Presl

(Pol-ee-STIK-um mew-NEE-tum)

Names: Polystichum means many rows, referring to the arrangement of the spore cases on the undersides of the fronds. Munitum means armed with teeth, referring to its toothed fronds. Western Sword Fern is also known as Sword Holly Fern, Giant Holly Fern, Christmas Fern, Pineland Sword Fern, or Chamisso’s Shield Fern.

Names: Polystichum means many rows, referring to the arrangement of the spore cases on the undersides of the fronds. Munitum means armed with teeth, referring to its toothed fronds. Western Sword Fern is also known as Sword Holly Fern, Giant Holly Fern, Christmas Fern, Pineland Sword Fern, or Chamisso’s Shield Fern.

Relationships: There are about 260 species of Polystichum worldwide with about 16 native to North America; and about 10 native to the Pacific Northwest.

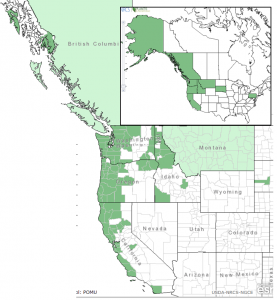

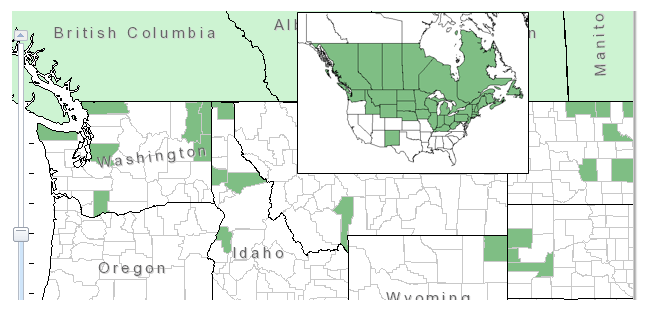

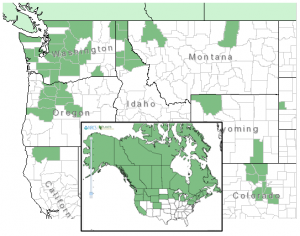

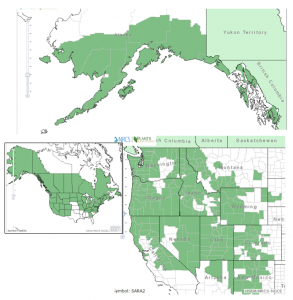

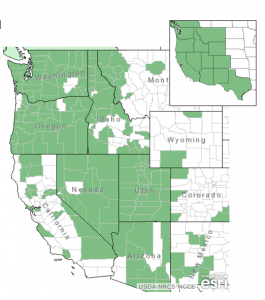

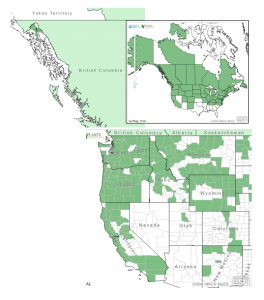

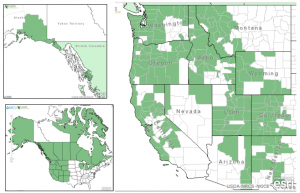

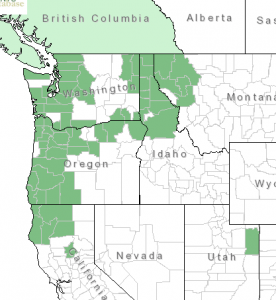

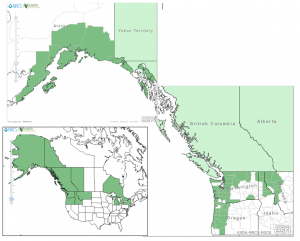

Distribution of Western Sword Fern from USDA Plants Database

Distribution: Western Sword Fern is found from southeast Alaska to the central California coast, mostly on the west of the Cascades; eastward to northern Idaho into northwest Montana. Disjunct populations have been found in South Dakota and on Guadalupe Island off Baja California.

Growth: Western Sword Fern grows up to 4.5 feet (1.5m) tall.

Habitat: It is usually found in moist forests, but it is probably the most adaptable of all our ferns and can take a bit more sun than other ferns and some dry periods. Wetland designation: FACU, it usually occurs in non-wetlands but occasionally is found in wetlands.

Sword Fern is very common in the understory in our westside forests.

Diagnostic Characters: Large, erect fronds form from a crown of scaly rhizomes. Fronds are once-pinnate with alternate pointed, sharp-toothed leaflets; each leaflet with a small lobe pointed forward at the base. Sori (spore cases) are large and round arranged in two rows on the undersides of the fronds halfway between the midvein and margins.

In the Landscape: Western Sword Fern is the most widespread and versatile of all our native ferns. Although at home in woodlands, it often adapts to drier, sunnier sites in landscapes. Its tall arching fronds are most impressive planted in drifts in a woodland garden. When grown in the sun, the fronds are dwarfed and more erect; and have pinnae (leaflets) that are crisped and crowded so that they overlap and appear overlapping. Young ferns are also more frilly-looking.

Phenology: Fronds partially unroll their “fiddleheads” by late May; by late July the spores are near maturity.

Phenology: Fronds partially unroll their “fiddleheads” by late May; by late July the spores are near maturity.

Sword Fern Fiddleheads.

Use by natives: The roots/rhizomes were generally viewed by natives as a famine food. (This plant probably should only be consumed in small quantities, if at all, due to possible presence of carcinogens or other toxins.) The rhizomes were peeled and then boiled or baked in a pit on hot rocks covered with fronds. The fronds were used frequently for lining baking pits and storage baskets; and were spread on drying racks to prevent berries from sticking. They were variously used for placemats, floor coverings, bedding; and for games, dancing skirts and other decorations. They are frequently used today in flower arrangements.

Use by natives: The roots/rhizomes were generally viewed by natives as a famine food. (This plant probably should only be consumed in small quantities, if at all, due to possible presence of carcinogens or other toxins.) The rhizomes were peeled and then boiled or baked in a pit on hot rocks covered with fronds. The fronds were used frequently for lining baking pits and storage baskets; and were spread on drying racks to prevent berries from sticking. They were variously used for placemats, floor coverings, bedding; and for games, dancing skirts and other decorations. They are frequently used today in flower arrangements.

Use by wildlife: Western Sword Fern is browsed by deer, elk, Black Bear and Mountain Beaver; frequently eaten by Roosevelt Elk on the Olympic Peninsula. The fronds may be used as nesting material for rodents.

Western Sword Fern outcrosses frequently and hybrids have been identified from crosses with Anderson’s Holly Fern (P. andersonii), Mountain Holly Fern, (P. scopulinum) California Sword Fern (P. californicum), Shasta Fern (P. lemmonii), and Narrowleaf Sword Fern, (P. imbricans)

Links:

Consortium of Pacific Northwest Herbaria

WTU Herbarium Image Collection, Plants of Washington, Burke Museum

E-Flora BC, Electronic Atlas of the Flora of British Columbia

Jepson Eflora, University of California

Ladybird Johnson Wildflower Center

USDA Forest Service-Fire Effects Information System

Hardy Fern Library

Native Plants Network, Propagation Protocol Database

Native American Ethnobotany, University of Michigan, Dearborn

Other Polystichum sp., native to the Pacific Northwest:

Narrowleaf Sword Fern, P. imbricans is similar to Western Sword Fern and once was classified as a variety of P. munitum. It is smaller (20-60cm) with overlapping, somewhat infolded leaflets and only scarcely scaly stipes (petioles). It is a better choice for a sunny spot.

Anderson’s Holly Fern, P. andersonii is much rarer; found in deep woods in the mountains. Fronds grow to 1 meter. It has a conspicuously chaffy fiddlehead and leaf stalk. Pinnae are deeply cut making it appear doubly pinnate. Bulblets form at the base of pinnae near the tip and may grow into a new plant when the frond touches the ground!

Anderson’s Holly Fern

Braun’s Holly Fern, P. braunii, is big (to 1m) and has twice pinnate leaves with no basal lobes. It grows in moist woodlands. (Native to British Columbia, southern Alaska, the Idaho panhandle—Listed as threatened or endangered in several eastern U.S. states).

California Sword Fern, P. californicum, has finely toothed leaflets rather than the prominently toothed leaflets in Western Sword Fern; each tooth is short, ending abruptly. It will grow in a variety of habitats from moist, shaded woods to open slopes, and dry, rocky terrain. It is rare in Washington & Oregon, listed as sensitive in Washington, only found in or near the Cascades in Pierce & Thurston counties).

Kruckeberg’s Holly Fern, P. kruckebergii is believed to be a fertile hybrid of P. lonchitis & P. lemmonii. It is found sporadically in the Cascades, Sierras, & Rocky Mountains on rocks and cliffs and is considered rare or imperiled in Alaska, Montana, Idaho, California and B.C.; and “of concern” in Oregon. Fronds are about 10-25cm long. Short leaflets are oval to triangular, overlapping and twisted; with teeth tipped with spines. It is named after Dr. Arthur Kruckeberg, the well-known botanist and native plant gardener and enthusiast.

Kwakiutl Holly Fern, P. kwakiutlii is known only from the type specimen, collected at Alice Arm, British Columbia in 1934. It is presumed to be one of the diploid progenitors of P. andersonii. It also produced bulblets, but differs from P. andersonii in its completely divided pinnae (leaflets). Kwakiutl is a name applied to the native people in British Columbia on Vancouver Island and surrounding areas.

Lemmon’s or Shasta Holly Fern, P. lemmonii: Fronds are twice pinnate; pinnae have no spines and are overlapping and twisted, making it appear cylindrical. This species grows in serpentine rock crevices; and is found sporadically in the Cascades from B.C. to northern California. It is only known from one site in B.C. where it is listed as threatened.

Northern Holly Fern, P. lonchitis, grows in mountains, often in rock crevices, throughout much of the northern hemisphere. Lonchitis is from the Greek logch meaning spear, referring to its spear-shaped leaves. It is once pinnate with spiny leaflets; resembling a miniature Sword Fern. It is listed as endangered in New York; and is on a review list in California.

Mountain Holly Fern or Rock Sword Fern, P. scopulinum is also like a smaller Sword Fern but is shinier and more leathery with spiny-toothed leaves. It is nearly bipinnate with long hairs on the teeth of each leaflet. It is found in dry coniferous forest or more commonly on cliffs and talus slopes. It is more frequent east of the Cascades and the Rocky Mountains; it also grows in eastern Canada.

Alaska Holly Fern, P. setigerum, is presumed to a hybrid between P. munitum and P. braunii. Fronds are 2-pinnate about the middle, finely spiny-toothed. It is found in lowland coastal forests in Alaska and B.C. It may be able find a niche in a cool, moist woodland garden.

Names: The name Sambucus is derived from the Greek sambuca, which was a stringed instrument supposed to have been made from elder wood. Racemosa refers to the elongated inflorescences, called racemes. It is thought the name elder comes the Anglo-saxon ‘auld,’ ‘aeld’ or ‘eller’, meaning fire, because the hollow stems were used as bellows to blow air into the center of a fire. Our Red Elderberry has also been known as S. callicarpa (callicarpa=beautiful fruit). Some identify our local plants as S. racemosa ssp. pubens var. arborescens; (pubens because of the downy pubescence beneath the leaves, and arborescens because of its tree-like form.) It also may be called Mountain Red Elderberry, Scarlet Elder or Elderberry, Racemed Elder, or Bunchberry Elder. A purplish-black-berried form, Rocky Mountain Elderberry, S. racemosa var. melanocarpa is also found through much of the west.

Names: The name Sambucus is derived from the Greek sambuca, which was a stringed instrument supposed to have been made from elder wood. Racemosa refers to the elongated inflorescences, called racemes. It is thought the name elder comes the Anglo-saxon ‘auld,’ ‘aeld’ or ‘eller’, meaning fire, because the hollow stems were used as bellows to blow air into the center of a fire. Our Red Elderberry has also been known as S. callicarpa (callicarpa=beautiful fruit). Some identify our local plants as S. racemosa ssp. pubens var. arborescens; (pubens because of the downy pubescence beneath the leaves, and arborescens because of its tree-like form.) It also may be called Mountain Red Elderberry, Scarlet Elder or Elderberry, Racemed Elder, or Bunchberry Elder. A purplish-black-berried form, Rocky Mountain Elderberry, S. racemosa var. melanocarpa is also found through much of the west.

In the Landscape: Red Elderberry is especially attractive in woodland gardens. Its vase-like, arborescent form creates an umbrella-like canopy over smaller woodland shrubs. Overgrown plants can be severely pruned. Red Elderberry is used for revegetation, erosion control, and wildlife plantings. It may be relatively tolerant of heavy metal contamination, so may be useful in restoring habitats around mining and smelting sites.

In the Landscape: Red Elderberry is especially attractive in woodland gardens. Its vase-like, arborescent form creates an umbrella-like canopy over smaller woodland shrubs. Overgrown plants can be severely pruned. Red Elderberry is used for revegetation, erosion control, and wildlife plantings. It may be relatively tolerant of heavy metal contamination, so may be useful in restoring habitats around mining and smelting sites.

Use by people: Natives steamed the berries on rocks and put them in a container stored underground or in water, eating them later in winter. Leaves, bark or roots were applied externally to abscesses, aching muscles, or sore joints. Roots or bark were chewed or made into a tea to induce vomiting or as a laxative. Flowers were boiled down to treat coughs and colds. Hollow stems were used for whistles, pipes and toy blowguns. Although they have sometimes been eaten fresh, it is advisable to always cook the berries before eating, raw berries may cause nausea. The seeds are considered poisonous. Cooked berries can be made into wines, sauces or jellies.

Use by people: Natives steamed the berries on rocks and put them in a container stored underground or in water, eating them later in winter. Leaves, bark or roots were applied externally to abscesses, aching muscles, or sore joints. Roots or bark were chewed or made into a tea to induce vomiting or as a laxative. Flowers were boiled down to treat coughs and colds. Hollow stems were used for whistles, pipes and toy blowguns. Although they have sometimes been eaten fresh, it is advisable to always cook the berries before eating, raw berries may cause nausea. The seeds are considered poisonous. Cooked berries can be made into wines, sauces or jellies.

Names: The name Sambucus is derived from the Greek sambuca, which was a stringed instrument supposed to have been made from elder wood. Nigra means black; caerulea means sky-blue. It is thought the name elder comes the Anglo-saxon ‘auld,’ ‘aeld’ or ‘eller’, meaning fire, because the hollow stems were used as bellows to blow air into the center of a fire. Blue Elderberry was sometimes known as S. glauca; it is more commonly known as Sambucus cerulea (or caerulea), but many botanists feel that it and the American Elderberry, Sambucus canadensis, are just a subspecies of the well-known European species, the Black Elder, Sambucus nigra.

Names: The name Sambucus is derived from the Greek sambuca, which was a stringed instrument supposed to have been made from elder wood. Nigra means black; caerulea means sky-blue. It is thought the name elder comes the Anglo-saxon ‘auld,’ ‘aeld’ or ‘eller’, meaning fire, because the hollow stems were used as bellows to blow air into the center of a fire. Blue Elderberry was sometimes known as S. glauca; it is more commonly known as Sambucus cerulea (or caerulea), but many botanists feel that it and the American Elderberry, Sambucus canadensis, are just a subspecies of the well-known European species, the Black Elder, Sambucus nigra.

Use by People: Elder trees were important in Celtic folklore and mythology; they were considered sacred to fairies and were used for making wands. The “Elder Wand” was one of the “Deathly Hallows” in the Harry Potter book series. In Europe, elderflowers are widely used to make syrups, cordials and liqueurs. The pith was by watchmakers for cleaning tools before intricate work. The fruit, on both continents, is often used for wine, jellies, candy, pies, and sauces. Northwest natives ate the berries fresh, dried, steamed, or boiled. Raw berries, especially if they are not fully ripe, may cause some people to experience an upset stomach. The bark and leaves were used to induce vomiting and as a laxative; externally applied, they were used for pain, bruises, swelling, and as an antiseptic. The flowers were made into a tea to treat cold and flu symptoms. The berries were used to make a black or purple dye; the stems to make an orange or yellow dye. Hollow twigs were used for flutes, whistles, pipes, blowguns and squirtguns; whistles were use to call elk. The soft wood was used as a twirling stick to make fire.

Use by People: Elder trees were important in Celtic folklore and mythology; they were considered sacred to fairies and were used for making wands. The “Elder Wand” was one of the “Deathly Hallows” in the Harry Potter book series. In Europe, elderflowers are widely used to make syrups, cordials and liqueurs. The pith was by watchmakers for cleaning tools before intricate work. The fruit, on both continents, is often used for wine, jellies, candy, pies, and sauces. Northwest natives ate the berries fresh, dried, steamed, or boiled. Raw berries, especially if they are not fully ripe, may cause some people to experience an upset stomach. The bark and leaves were used to induce vomiting and as a laxative; externally applied, they were used for pain, bruises, swelling, and as an antiseptic. The flowers were made into a tea to treat cold and flu symptoms. The berries were used to make a black or purple dye; the stems to make an orange or yellow dye. Hollow twigs were used for flutes, whistles, pipes, blowguns and squirtguns; whistles were use to call elk. The soft wood was used as a twirling stick to make fire.

Names: Symphori- means “bear together;” –carpos means fruits– referring to the clustered fruits. Albus meaning white, and the common name, Snowberry also refers to the white fruits. This species is sometimes known as Waxberry, White Coralberry, or White, Thin-leaved, or Few-flowered Snowberry.

Names: Symphori- means “bear together;” –carpos means fruits– referring to the clustered fruits. Albus meaning white, and the common name, Snowberry also refers to the white fruits. This species is sometimes known as Waxberry, White Coralberry, or White, Thin-leaved, or Few-flowered Snowberry.

Growth: This species usually grows 3-9 feet (1-2m) tall.

Growth: This species usually grows 3-9 feet (1-2m) tall.

Phenology: Bloom time: May-August; Fruit ripens: September-October, persisting through winter.

Phenology: Bloom time: May-August; Fruit ripens: September-October, persisting through winter.

Names: Black Twinberry is also known as Involucred, Bracted, Bearberry, Fly or Fourline Honeysuckle; or Coast Twinberry. Involucrata refers to the involucres, or bracts that surround the flowers and fruit. Twinberry refers to the 2 berries surrounded by the bracts.

Names: Black Twinberry is also known as Involucred, Bracted, Bearberry, Fly or Fourline Honeysuckle; or Coast Twinberry. Involucrata refers to the involucres, or bracts that surround the flowers and fruit. Twinberry refers to the 2 berries surrounded by the bracts.

Diagnostic Characters: Black Twinberry has opposite leaves that are broadly lance-shaped. It has paired, tubular, yellow flowers arising from the leaf axils. The flowers are 5-lobed, surrounded by large, green or purple bracts. Fruits are shiny, black “twin” berries surrounded by purplish-red bracts. Young, green twigs are 4-angled in cross-section.

Diagnostic Characters: Black Twinberry has opposite leaves that are broadly lance-shaped. It has paired, tubular, yellow flowers arising from the leaf axils. The flowers are 5-lobed, surrounded by large, green or purple bracts. Fruits are shiny, black “twin” berries surrounded by purplish-red bracts. Young, green twigs are 4-angled in cross-section. In the Landscape: It is an attractive shrub and should be used more in the garden. It is a great “edge” species when planted between a forest and more open area. It can be used in a hedgerow or in a Rain Garden. Its fresh, green leaves are similar to Indian Plum; and its dainty, yellow flowers and colorful bracts add interest throughout spring, summer, and fall. Black Twinberry is great for reclamation plantings on riparian sites, in wet meadows and in forests.

In the Landscape: It is an attractive shrub and should be used more in the garden. It is a great “edge” species when planted between a forest and more open area. It can be used in a hedgerow or in a Rain Garden. Its fresh, green leaves are similar to Indian Plum; and its dainty, yellow flowers and colorful bracts add interest throughout spring, summer, and fall. Black Twinberry is great for reclamation plantings on riparian sites, in wet meadows and in forests.

Red Twinberry

Red Twinberry Names: Hairy Honeysuckle is also called Pink Honeysuckle or California (Pink or Hairy) Honeysuckle. Hispidula means covered with bristly hairs. The common name, honeysuckle, comes from the fact that children enjoy sucking nectar from the base of the flowers for a sweet treat. The name Lonicera is derived from Adamus Lonicerus (Adam Lonitzer), a German botanist, author of the herbal, Kräuterbuch (1557).

Names: Hairy Honeysuckle is also called Pink Honeysuckle or California (Pink or Hairy) Honeysuckle. Hispidula means covered with bristly hairs. The common name, honeysuckle, comes from the fact that children enjoy sucking nectar from the base of the flowers for a sweet treat. The name Lonicera is derived from Adamus Lonicerus (Adam Lonitzer), a German botanist, author of the herbal, Kräuterbuch (1557).

Names: Honeysuckles have long been a garden favorite, grown mostly for their sweetly-scented, nectar-producing flowers. The common name, honeysuckle, comes from the fact that children enjoy sucking nectar from the base of the flowers for a sweet treat. This species is also known as Orange Honeysuckle, Northwest Honeysuckle, or Western Trumpet. The name Lonicera is derived from Adamus Lonicerus (Adam Lonitzer), a German botanist, author of the herbal, Kräuterbuch (1557). Ciliosa, which means having small, fringe-like hairs like eyelashes, refers to the hairy edges of the leaves.

Names: Honeysuckles have long been a garden favorite, grown mostly for their sweetly-scented, nectar-producing flowers. The common name, honeysuckle, comes from the fact that children enjoy sucking nectar from the base of the flowers for a sweet treat. This species is also known as Orange Honeysuckle, Northwest Honeysuckle, or Western Trumpet. The name Lonicera is derived from Adamus Lonicerus (Adam Lonitzer), a German botanist, author of the herbal, Kräuterbuch (1557). Ciliosa, which means having small, fringe-like hairs like eyelashes, refers to the hairy edges of the leaves.

Names: The genus name, Oplopanax, is derived from hoplon, meaning weapon and panakos meaning panacea or “all-heal”—referring to the medicinal qualities of these shrubs and their relationship to the well-known Asian herb, Ginseng, Panax ginseng. Oplopanax is sometimes misspelled, Ophlopanax. Both the common name and specific epithet, horridus, refer to its spiny, wicked-looking appearance. Scientific synonyms include: Echinopanax horridum or horridus, Fatsia horridum, Panax horridum, and Ricinophyllum horridum.

Names: The genus name, Oplopanax, is derived from hoplon, meaning weapon and panakos meaning panacea or “all-heal”—referring to the medicinal qualities of these shrubs and their relationship to the well-known Asian herb, Ginseng, Panax ginseng. Oplopanax is sometimes misspelled, Ophlopanax. Both the common name and specific epithet, horridus, refer to its spiny, wicked-looking appearance. Scientific synonyms include: Echinopanax horridum or horridus, Fatsia horridum, Panax horridum, and Ricinophyllum horridum.

Phenology: Bloom time: May-July; Fruit ripens: June-August, persisting over winter.

Phenology: Bloom time: May-July; Fruit ripens: June-August, persisting over winter.