Oregon White Oak Beech Family–Fagaceae

Quercus garryana Douglas ex Hook.

(KWER-kus gair-ee-AH-nuh)

Names: Also called Garry Oak, Oregon White Oak was named after Nicholas Garry, a deputy governor for the Hudson’s Bay Company.

Relationships: There are hundreds of oak species in the temperate regions of the world, about 60 native to North America. They are divided into two main groups: red oaks and white oaks. Red Oak leaves usually have pointed lobes, their nuts are bitter and must have the tannins leached out before they are edible. Squirrels bury these acorns for consuming in late winter or spring. White oak leaves have rounded lobes, their nuts are not as bitter. Squirrels may eat these nuts as soon as they are ripe. Evergreen oaks are often called “live oaks.” Several species are native to California.

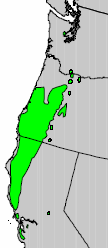

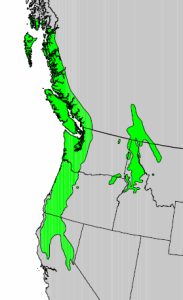

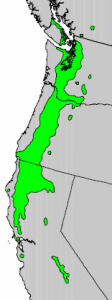

Distribution of Oregon White Oak from USGS ( “Atlas of United States Trees” by Elbert L. Little, Jr. )

Distribution: Oregon White Oak is found from southern British Columbia to northern California, mostly on the west side of the Cascade Mountains.

Growth: This species grows slowly to 80-100 feet (25-30m). It may live 250-500 years.

Habitat: Oregon White Oak grows on dry, rocky slopes and in open savannahs. Many native oak prairies, and their associated ecosystem, have disappeared and continue to decline due to urban development, fire suppression and overgrazing. There is evidence that native people in the Willamette Valley burned the Oregon White Oak savannahs nearly every year in the late summer or early fall to prevent the encroachment of faster growing conifers.

Diagnostic Characters: Oregon White Oak is easily identified by its leaves with rounded lobes. It produces a typical acorn. The bark is light gray with thick furrows and ridges.

In the landscape, Oregon White Oak is an attractive addition to parks and spacious yards. Its rounded crown and intricate branching pattern adds interest to the winter landscape.

Phenology: Bloom Period: March to June. Acorns ripen early August to November. The heavy nuts fall to the ground and are often disseminated by animals, including people.

Propagation: Acorns germinate freely in moist soil. Nuts should not be allowed to dry out and need to be protected from rodents. Because of a large taproot, the best trees grow from acorns allowed to grow naturally and never moved. For the same reason, seedlings should be transplanted to their permanent location as soon as possible.

Use by people: Native people that lived near numerous oaks used the acorns as food. Those that ate large quantities would soak the nuts to leach out the tannins or they would bury them in baskets, in mud, all winter and eat them in the spring. Small quantities could be consumed without preparation. The bark was used in a preparation to treat tuberculosis. Today Oregon White Oak is used for furniture, flooring and other items. It also is good for firewood.

Use by people: Native people that lived near numerous oaks used the acorns as food. Those that ate large quantities would soak the nuts to leach out the tannins or they would bury them in baskets, in mud, all winter and eat them in the spring. Small quantities could be consumed without preparation. The bark was used in a preparation to treat tuberculosis. Today Oregon White Oak is used for furniture, flooring and other items. It also is good for firewood.

Use by wildlife: Oaks are the most important genus of trees for wildlife in the United States. The nutritious acorns that they produce provide an important food source in winter when other foods are scarce. Deer, bear, raccoons and many small mammals eat the acorns. The Western Gray Squirrel, which is listed as a threatened species in Washington State, is largely dependent upon Oregon White Oak trees. At Fort Lewis near Tacoma in Washington State, efforts are being made to preserve the squirrel’s declining oak prairie habitat. In return for providing a nutritious food, squirrels and other animals aid in the reproduction of oak trees by dispersing and burying the acorns. Birds that eat Oregon White Oak acorns include Wild Turkeys, Band-tailed Pigeons, Woodpeckers, Jays as well as many others. Oregon White Oak provides cover and shade for many species of wildlife.

Use by wildlife: Oaks are the most important genus of trees for wildlife in the United States. The nutritious acorns that they produce provide an important food source in winter when other foods are scarce. Deer, bear, raccoons and many small mammals eat the acorns. The Western Gray Squirrel, which is listed as a threatened species in Washington State, is largely dependent upon Oregon White Oak trees. At Fort Lewis near Tacoma in Washington State, efforts are being made to preserve the squirrel’s declining oak prairie habitat. In return for providing a nutritious food, squirrels and other animals aid in the reproduction of oak trees by dispersing and burying the acorns. Birds that eat Oregon White Oak acorns include Wild Turkeys, Band-tailed Pigeons, Woodpeckers, Jays as well as many others. Oregon White Oak provides cover and shade for many species of wildlife.

Sadler’s Oak, Quercus sadleriana, and Huckleberry Oak, Q. vaccinifolia are shrubby evergreen oaks that are native to southern Oregon; these make good additions to the landscape due to their small size and value to wildlife.

Links:

Consortium of Pacific Northwest Herbaria

WTU Herbarium Image Collection, Plants of Washington, Burke Museum

E-Flora BC, Electronic Atlas of the Flora of British Columbia

Jepson Manual, University of California

Ladybird Johnson Wildflower Center

USDA Forest Service-Fire Effects Information System

Native American Ethnobotany, University of Michigan, Dearborn