Oregon Ash The Olive Family–Oleaceae

(FRAKS-ih-nus lat-ih-FOAL-ee-uh)

Names: Latifolia means “wide leaves.” Oregon Ash has wider leaflets than most Ashes.

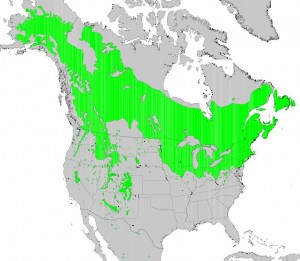

Relationships: There are about 65 species of Ashes, mostly in the temperate regions of the northern hemisphere. About 16 species occur in North America.

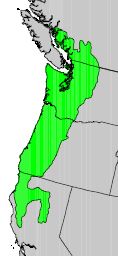

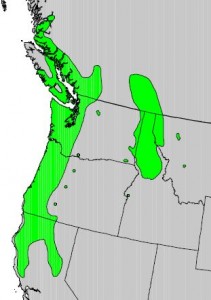

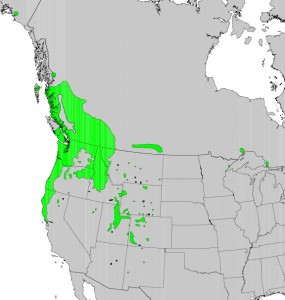

Distribution: Oregon Ash is found from the southern coast of British Columbia, west of the Cascades in Washington and Oregon, to the coast ranges and Sierra Nevadas of California.

Growth: Oregon Ash grows to about 75 feet (25m). It grows quickly for the first 80 years, then more slowly—living to about 250 years.

Habitat: This tree grows in moist to wet soils near streams, lakes and in flood plains.

Wetland Designation: FACW, Facultative wetland, it usually occurs in wetlands but occasionally occurs in non-wetlands.

Diagnostic Characters: Oregon Ash is our only tree with compound leaves, making it easy to identify. The oppositely arranged, pinnately compound leaves have 5-7 leaflets. Flowers are small and inconspicuous, appearing before the leaves. The seeds are single samaras, like a half of a maple seed, with long (3-5cm) wings, borne in large, drooping clusters.

In the Landscape: Oregon Ash is perhaps my least favorite of our native trees. The new growth is susceptible to aphids. It is, however, useful for revegetating wet areas that are flooded periodically. Autumn is its most aesthetic season, when female trees produce attractive seed clusters, followed by bright yellow fall foliage.

Phenology: Bloom Period: March-May. Samaras ripen: August-September.

Propagation: Seeds are best collected slightly green before fully dry on the tree and sown immediately outside or in a cold frame. Otherwise they require a cool, moist stratification at 40ºF (4ºC) for 90 days.

Use by people: Natives used Oregon Ash wood for canoe paddles and digging sticks. Today the hard wood is used for tool handles, furniture, sports equipment, and barrels. It also makes good firewood.

Use by wildlife: The winged seeds of Oregon Ash are eaten by a birds and small mammals. The foliage is food for butterfly larvae and may be consumed by passing browsers.

Links:

Consortium of Pacific Northwest Herbaria

WTU Herbarium Image Collection, Plants of Washington, Burke Museum

E-Flora BC, Electronic Atlas of the Flora of British Columbia

Jepson Eflora, University of California

Ladybird Johnson Wildflower Center

Native American Ethnobotany, University of Michigan, Dearborn