Names: Thimbleberries have a hollow core, like raspberries, making the berries easy to fit on the tip of a finger like a thimble. Rubus is derived from ruber, a latin word for red. Although parviflorus means small-flowered, the flowers of this species are among the largest of any Rubus species; it may get its name from a comparison to white wild roses. This species may also be called Western Thimbleberry, Western Thimble Raspberry, or White-flowering Raspberry.

Names: Thimbleberries have a hollow core, like raspberries, making the berries easy to fit on the tip of a finger like a thimble. Rubus is derived from ruber, a latin word for red. Although parviflorus means small-flowered, the flowers of this species are among the largest of any Rubus species; it may get its name from a comparison to white wild roses. This species may also be called Western Thimbleberry, Western Thimble Raspberry, or White-flowering Raspberry.

Relationships: Rubus is a large genus sometimes collectively known as brambles. It has between 400 and 750 species, including blackberries, raspberries, dewberries, and cloudberries. Rubus is considered taxonomically complex due to frequent hybridization and a high degree of polyploidy. It occurs primarily in northern temperate regions, but can be found on all continents, except Antarctica. Many are grown commercially and several cultivated varieties are prized for their large, juicy berries, including Boysenberries, Loganberries, and Marionberries. The berries are actually aggregates of drupelets. There are about 200 species native to North America. In the Pacific Northwest, the three most important native species are Blackcap Raspberry, Salmonberry, and Thimbleberry. Two of our worst nonnative invaders belong to this genus, Himalayan Blackberry, R. armeniacus (R. discolor), and Evergreen or Cutleaf Blackberry, R. laciniatus. Although they have delicious berries, and are excellent wildlife habitat, these species should be controlled as much as possible or they quickly take over disturbed habitats.

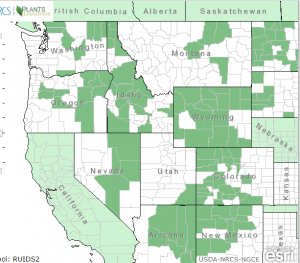

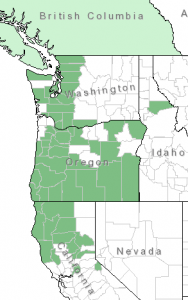

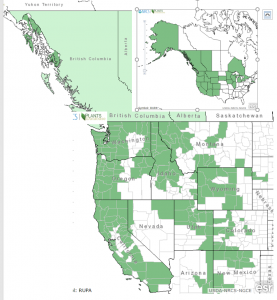

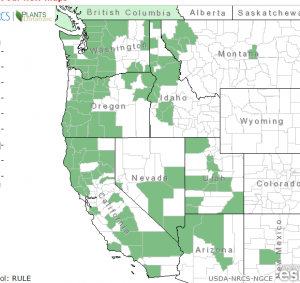

Distribution of Thimbleberry from USDA Plants Database

Distribution: Thimbleberry is native from southeast Alaska to northern Mexico; eastward throughout the Rocky Mountain states and provinces to New Mexico; through South Dakota to the Great Lakes region.

Growth: This species grows from 2-9 feet (0.5-3m) tall.

Habitat: It is found in moist to dry open woods, edges, open fields, and along shorelines. Wetland designation: FAC-, Facultative, it is equally likely to occur in wetlands or non-wetlands.

Diagnostic Characters: Thimbleberry stems have no prickles, and gray, shedding bark. Leaves are large, lobed, like maple leaves and fuzzy on both sides. Flowers are white and large (about 4 cm); borne 3-7 in a terminal cluster. The fruit is an aggregate of small, red, hairy drupelets in the shape of a domed cap.

Diagnostic Characters: Thimbleberry stems have no prickles, and gray, shedding bark. Leaves are large, lobed, like maple leaves and fuzzy on both sides. Flowers are white and large (about 4 cm); borne 3-7 in a terminal cluster. The fruit is an aggregate of small, red, hairy drupelets in the shape of a domed cap.

In the landscape: Although some may regard it as a pest, Thimbleberry adapts better to an ornamental landscape than its prickly, more aggressive cousins. Its white flowers are bright and cheerful. Its large, maple-like leaves make a bold contrast to finer textured shrubs. In fall, leaves turn a bright, golden yellow. Thimbleberry is especially attractive on hillsides with dappled shade.

Phenology: Bloom time: May-June. Fruit ripens: July-September.

Propagation: Stratify seeds warm for 90 days then cold at 40º F (4º C) for 90 days; exposure to sulfuric acid or sodium hyperchlorite solutions prior to cold stratification may improve germination. Thimbleberry can be vegetatively propagated by cuttings, layering or division. It spreads through underground rhizomes and resprouts from root crowns after a disturbance.

Use by People: Natives ate the young shoots, raw in early spring. The berries were eaten fresh, mixed with other berries. Some tribes collected unripe berries and stored them in baskets or cedar-bark bags until ripe; others dried them like salal berries, although some considered them too soft for drying. The large leaves made handy containers for collecting berries and were also used for wrapping and storing elderberries. The boiled bark was used as soap. Today the berries, considered too seedy for jam, are sometimes made into jelly. Dried, powdered leaves were applied to wounds and burns to prevent scarring. A tea was made from the leaves for medicinal purposes. Hikers call it the soft fuzzy leaves “nature’s toilet paper.”

Use by wildlife: The brambles rank at the very top of summer foods for wildlife, especially birds: grouse, pigeons, quail, grosbeaks, jays, robins, thrushes, towhees, waxwings, sparrows, to name just a few. The berries are also popular with raccoons, opossums, skunks, foxes, squirrels, chipmunks and other rodents. The leaves and stems are eaten extensively by deer and rabbits. Bear, beaver and marmots eat fruit, bark and twigs. Flowers are usually pollinated by insects.

Links:

Consortium of Pacific Northwest Herbaria

WTU Herbarium Image Collection, Plants of Washington, Burke Museum

E-Flora BC, Electronic Atlas of the Flora of British Columbia

Jepson Eflora, University of California

Ladybird Johnson Wildflower Center

USDA Forest Service-Fire Effects Information System

Native Plants Network, Propagation Protocol Database

Native American Ethnobotany, University of Michigan, Dearborn

Names: Blackcap Raspberry is also known as Whitebark Raspberry or simply Black Raspberry. Rubus, derived from ruber, a latin word for red, is the genus of plants generally called brambles. It includes blackberries, raspberries, dewberries, and cloudberries. Rasp- may have come from a 15th century word, raspis, which means “a fruit from which a drink could be made.” “Leucodermis means white skin, or “whitebark”—referring to the very glaucous (whitish bloom) on its stems.

Names: Blackcap Raspberry is also known as Whitebark Raspberry or simply Black Raspberry. Rubus, derived from ruber, a latin word for red, is the genus of plants generally called brambles. It includes blackberries, raspberries, dewberries, and cloudberries. Rasp- may have come from a 15th century word, raspis, which means “a fruit from which a drink could be made.” “Leucodermis means white skin, or “whitebark”—referring to the very glaucous (whitish bloom) on its stems.

Phenology: Bloom time: May-June; Fruit ripens: Jul-Aug.

Phenology: Bloom time: May-June; Fruit ripens: Jul-Aug.