Western White Pine The Pine Family–Pinaceae

Pinus monticola Douglas ex D. Don

(PIE-nus mon-tih-KOE-luh)

Names: Western White Pine is a 5-needled, soft pine or white pine. White Pines are so named because of the color of their wood. Monticola means “mountain dweller.”

Relationships: There are about 115 species of pines worldwide, 35 in North America. The needles of pines are borne in bundles (or fascicles). Pines are separated into two groups: soft pines, which usually have needles in bundles of 5; and hard pines, which usually have needles in bundles of 2 or 3. Western White Pine is our one common (5-needled ) soft pine. We also have two common hard pines (one with 2 needles and one usually with 3 needles).

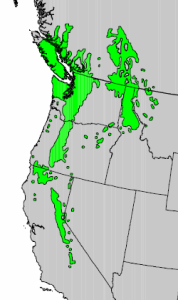

Distribution of Western White Pine from USGS ( “Atlas of United States Trees” by Elbert L. Little, Jr. )

Distribution: Western White Pine is native to southern British Columbia, western Washington, northern Idaho, western Montana, the Cascade Mountains of Oregon and the Sierras of California.

Growth: They are fast growing when young and may grow 1½-2 feet (45-60cm) in a year. In cultivation, they sometimes reach 135 feet (40m). The largest, growing in Oregon, near Fish Lake east of Medford, is over 220 feet (67m) tall. Most of the largest, however, are in Idaho, growing in remnants of forests depleted by earlier logging and the devastating disease, White Pine Blister Rust. Some historical trees may have reached close to 240 feet (73m). White Pines can live over 400 years.

Habitat: Western White Pines grow in moist valleys to fairly dry, open sites.

Wetland designation: FACU, Facultative upland, it usually occurs in non-wetlands.

Diagnostic Characters: White pines are easily recognized by their long, soft, slender needles in bundles of five. They are nice to stroke. The cones of white pines although still woody, are much softer than the cones of hard pines. The scales on cones of white pines have no prickles and are often dotted with spots of white resin.

Diagnostic Characters: White pines are easily recognized by their long, soft, slender needles in bundles of five. They are nice to stroke. The cones of white pines although still woody, are much softer than the cones of hard pines. The scales on cones of white pines have no prickles and are often dotted with spots of white resin.

In the landscape: Western White Pine has an attractive, pyramidal habit. It is best in large open spaces. Because the cones can drip pitch in warm weather, it should not be planted next to patios or where cars will be parked. The possibility of infection by White Pine Blister Rust is increased if the pathogen’s alternate hosts, currants or gooseberries (Ribes sp.) are growing within 10 miles. However, the virtues of this pine make it worth growing despite the risk. Resistant strains are becoming available. Pines produce new shoots in the spring, called “candles.” If it is desired to control the growth of pines, it is better to pinch back the elongating candles in the spring rather than shearing or pruning.

In the landscape: Western White Pine has an attractive, pyramidal habit. It is best in large open spaces. Because the cones can drip pitch in warm weather, it should not be planted next to patios or where cars will be parked. The possibility of infection by White Pine Blister Rust is increased if the pathogen’s alternate hosts, currants or gooseberries (Ribes sp.) are growing within 10 miles. However, the virtues of this pine make it worth growing despite the risk. Resistant strains are becoming available. Pines produce new shoots in the spring, called “candles.” If it is desired to control the growth of pines, it is better to pinch back the elongating candles in the spring rather than shearing or pruning.

Phenology: Bloom Period: Late June to Mid-July. Cones mature in August to September; seed dispersal begins in September.

Propagation: Stratify seed at 40ºF (4ºC) for 120 days and sow on the surface of the soil. Fresh seed is best. Although seed may remain viable for up to 4 years, germination rates decrease dramatically in older seeds. Cuttings are difficult but are possible using single leaf fascicles with the base of a short shoot taken from very young trees. Pinus monticola has also been propagated using micropropagation techniques.

Use by People: Western White Pine was an important timber tree, particularly in northern Idaho and surrounding areas prior to the introduction of infected seedlings from Europe. (The rust disease had previously been introduced to Europe from Asia.) Many early pioneers were familiar with its eastern cousin, Eastern White Pine, Pinus strobus, and were happy to discover this larger relative. It is prized for its soft, easily worked, fine textured wood. It is good for moldings and window and door frames. Wooden matches were made from Western White Pine in the 1920’s and 30’s. Native Americans boiled the bark and used it medicinally for stomach aches, and tuberculosis; it was also applied on cuts and sores. The pitch was chewed like gum.

Use by Wildlife: Nationwide, pines are second only to oaks in their food value to wildlife. In the Pacific region, pines are the most valuable. They have nutritious, oily seeds that are favored by many birds, especially Clark Nutcracker, crossbills, grosbeaks, jays, nuthatches, chickadees, and woodpeckers. Many small mammals, such as chipmunks and squirrels also eat the seeds. Foliage is eaten by grouse and deer. Porcupines and small rodents eat the bark and wood. Pine needles are a favorite material for making nests. Large pines provide excellent sites for roosting and nesting; small pines provide good cover for many animals.

There are two other soft pines in or near our region. The Whitebark Pine, Pinus albicaulis is an alpine species commonly found in the Krummholz zone on the eastern crest of the Cascades, but a few grow in the rainshadow side of the Olympic peaks. The Sugar Pine, Pinus lambertiana found in southern Oregon and California has the longest cones of any American conifer, 10-26 inches (25-65cm) long!

Links:

Consortium of Pacific Northwest Herbaria

WTU Herbarium Image Collection, Plants of Washington, Burke Museum

E-Flora BC, Electronic Atlas of the Flora of British Columbia

Jepson Manual, University of California

Ladybird Johnson Wildflower Center

USDA Forest Service-Fire Effects Information System

Virginia Tech ID Fact Sheet + Landowner Fact Sheet

Native Plants Network, Propagation Protocol Database

Native American Ethnobotany, University of Michigan, Dearborn