Western Larch The Pine Family– Pinaceae

Larix occidentalis Nutt.

(Lair-iks auk-sih-DEN-tay-lis)

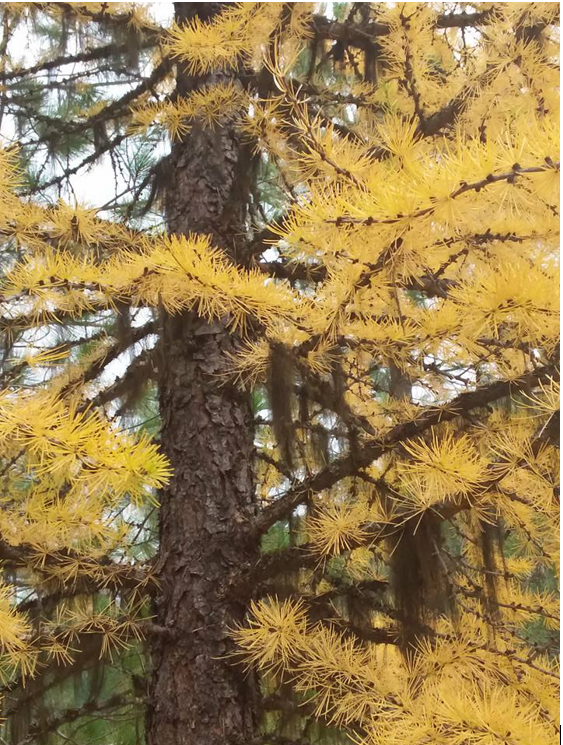

Unlike most conifers, Larches are deciduous; the needles turn a golden color in the fall before they are shed.

Unlike most conifers, Larches are deciduous; the needles turn a golden color in the fall before they are shed.

Names: Larches are sometimes called Tamaracks. The term “occidentalis” means western.

Relationships: There are eleven species in the northern hemisphere, three in North America.

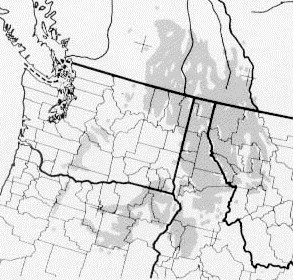

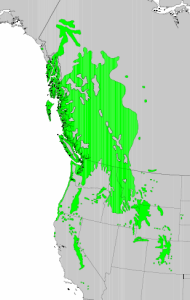

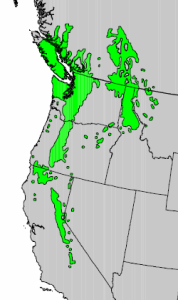

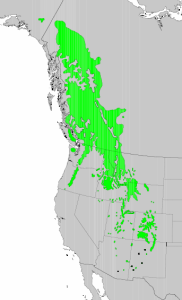

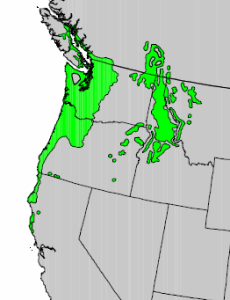

Distribution: Western Larch draws many tourists every autumn to the eastern slopes of the Cascade Mountains to see entire mountainsides turn golden. From the Cascades in British Columbia, Washington and Oregon, its range extends eastward to the Rocky Mountains of B.C., northern Idaho and western Montana.

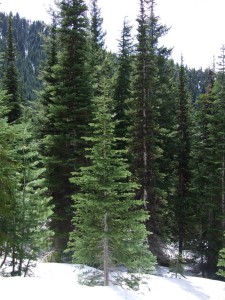

Growth: Western Larch grows rapidly when young. It can reach 100-175 feet (30-55m) tall; in gardens it usually grows 30-50 feet (10-15m). It may live to be over 700 years old.

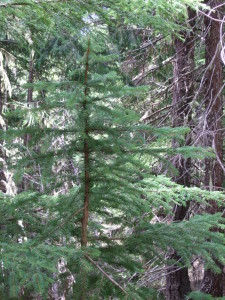

Habitat: It prefers moist, north or east facing mountain slopes but will also grow on dry, rocky soils. It is adapted to cool temperatures with moderate precipitation, often as snow. It is not tolerant of shade. Its thick bark and high canopy make it well adapted to fire.

Habitat: It prefers moist, north or east facing mountain slopes but will also grow on dry, rocky soils. It is adapted to cool temperatures with moderate precipitation, often as snow. It is not tolerant of shade. Its thick bark and high canopy make it well adapted to fire.

Wetland designation: FACU+, Facultative upland, it usually occurs in non-wetlands.

Diagnostic Characters: Western Larch is easy to recognize by its short (1-1.8” or 2.5-4.5cm) spring-green needles, 15-30 per spur. The foliage is similar in appearance to true cedars. New cones are bright red. In winter, it may be recognized by the pegs on its twigs that once held the needles—it is often mistaken for a dead evergreen. Mature cones are 1-1.5 inches (2.5-3cm) long with many scales with long pointed bracts. They often persist on the branches for several years. The bark is reddish brown and scaly, similar to Ponderosa Pine.

Diagnostic Characters: Western Larch is easy to recognize by its short (1-1.8” or 2.5-4.5cm) spring-green needles, 15-30 per spur. The foliage is similar in appearance to true cedars. New cones are bright red. In winter, it may be recognized by the pegs on its twigs that once held the needles—it is often mistaken for a dead evergreen. Mature cones are 1-1.5 inches (2.5-3cm) long with many scales with long pointed bracts. They often persist on the branches for several years. The bark is reddish brown and scaly, similar to Ponderosa Pine.

In the Landscape: Western Larch provides an ever-changing visual display. In spring, it is a verdant green with bright red new cones. As fall approaches the needles turn a bright golden yellow. In winter, its many cones create a polka dot pattern against the sky on its slender pyramidal form.

Phenology: Bloom Period: Mid-April to early June. Cones mature in mid to late August to September; seed dispersal begins in September.

Phenology: Bloom Period: Mid-April to early June. Cones mature in mid to late August to September; seed dispersal begins in September.

Propagation: Stratify at 40ºF (4ºC) for 60 days. Germination is best on the surface of mineral soils. Seedlings transplant easily in the fall.

Use by People: Western Larch is a valuable lumber tree. It has the densest wood of the northwest conifers it is often used to make boxes and crates. Another important economic product is Larch gum; it is similar to gum arabic and is used as an emulsifier or stabilizer in foods and medicine.

Use by Wildlife: Western Larch provides food and cover for a variety of animals. Squirrels and other small mammals eat the seeds and seedlings. It is also a preferred nesting site for woodpeckers and other cavity nesters.

Links for Larix occidentalis:

Consortium of Pacific Northwest Herbaria

WTU Herbarium Image Collection, Plants of Washington, Burke Museum

E-Flora BC, Electronic Atlas of the Flora of British Columbia

Ladybird Johnson Wildflower Center

USDA Forest Service-Fire Effects Information System

Virginia Tech ID Fact Sheet + Landowner Fact Sheet

Native Plants Network, Propagation Protocol Database

Native American Ethnobotany, University of Michigan, Dearborn

National Register of Big Trees

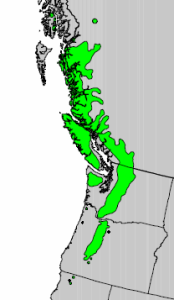

Subalpine Larch, Larix lyallii, is a subalpine species found in the North Cascades and the Northern Rockies. This species has not been cultivated successfully to any extent. Any attempt to propagate this tree through collection of seeds or seedlings should be done with great care so as not to disrupt the fragile habitat in which it grows.

Grouse and other game birds are the primary consumers of Alpine Larch needles.

Links for Larix lyallii:

Consortium of Pacific Northwest Herbaria

WTU Herbarium Image Collection, Plants of Washington, Burke Museum

E-Flora BC, Electronic Atlas of the Flora of British Columbia

Ladybird Johnson Wildflower Center

USDA Forest Service-Fire Effects Information System