Blackcap Raspberry The Rose Family—Rosaceae

Rubus leucodermis Douglas ex Torr. & A. Gray

(ROO-bus loy-ko-DERM-is)

Names: Blackcap Raspberry is also known as Whitebark Raspberry or simply Black Raspberry. Rubus, derived from ruber, a latin word for red, is the genus of plants generally called brambles. It includes blackberries, raspberries, dewberries, and cloudberries. Rasp- may have come from a 15th century word, raspis, which means “a fruit from which a drink could be made.” “Leucodermis means white skin, or “whitebark”—referring to the very glaucous (whitish bloom) on its stems.

Names: Blackcap Raspberry is also known as Whitebark Raspberry or simply Black Raspberry. Rubus, derived from ruber, a latin word for red, is the genus of plants generally called brambles. It includes blackberries, raspberries, dewberries, and cloudberries. Rasp- may have come from a 15th century word, raspis, which means “a fruit from which a drink could be made.” “Leucodermis means white skin, or “whitebark”—referring to the very glaucous (whitish bloom) on its stems.

Relationships: Rubus is a large genus with between 400 and 750 species. Rubus is considered taxonomically complex due to frequent hybridization and a high degree of polyploidy. It occurs primarily in northern temperate regions, but can be found on all continents, except Antarctica. Many are grown commercially and several cultivated varieties are prized for their large, juicy berries, including Boysenberries, Loganberries, and Marionberries. The berries are actually aggregates of drupelets. There are about 200 species native to North America. In the Pacific Northwest, the three most important native species are Blackcap Raspberry, Salmonberry, and Thimbleberry. There are several smaller species, as well.

Two of our worst nonnative invaders belong to this genus, Himalayan Blackberry, R. armeniacus (R. discolor), and Evergreen or Cutleaf Blackberry, R. laciniatus. Although they have delicious berries, and are excellent wildlife habitat, these species should be controlled as much as possible or they quickly take over disturbed habitats.

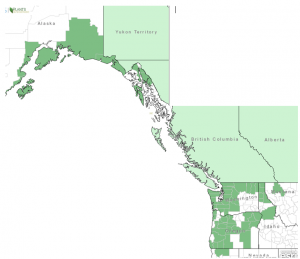

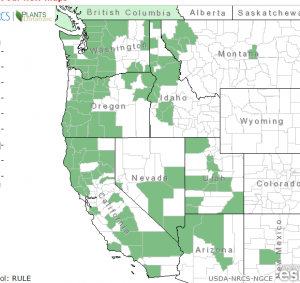

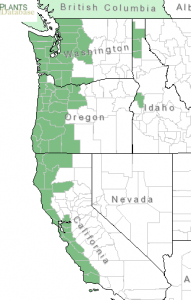

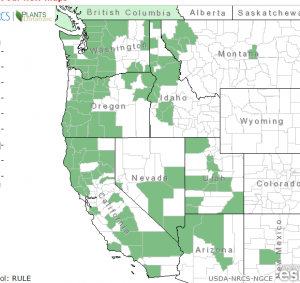

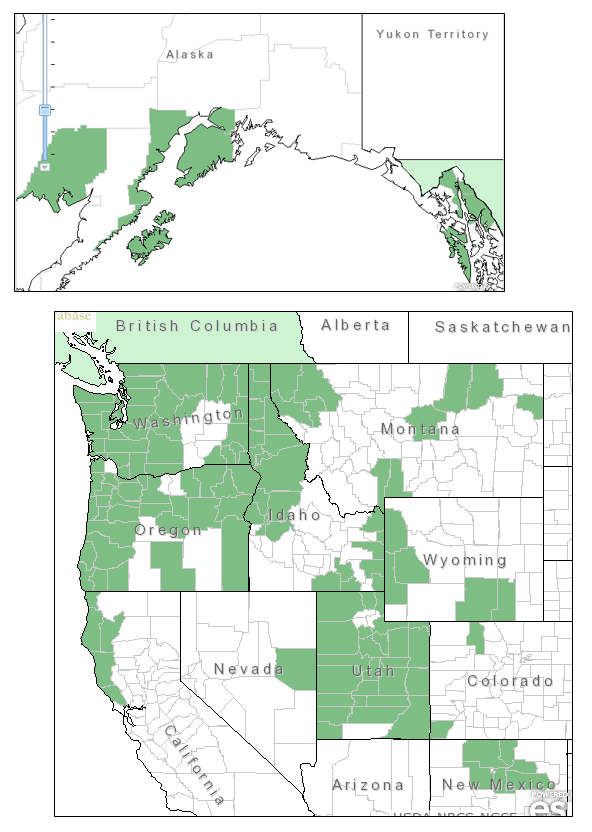

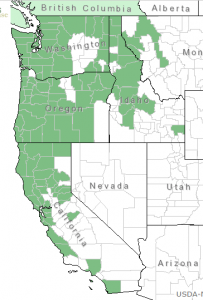

Distribution of Blackcap Raspberry from USDA Plants Database

Distribution: This species is native from central British Columbia (possibly into Southeast Alaska) to southern California; to eastern Montana, Utah, Arizona, and New Mexico.

Growth: Black Raspberry canes arch up to 6 feet, (2m) tall.

Habitat: It grows mostly in disturbed sites, fields, and open forests.

Diagnostic Characters: Its stems are covered by a whitish or bluish, waxy bloom, and are armed with flattened, hooked prickles. Leaves usually have 3 sharp-toothed leaflets with white undersides. Flowers are borne in clusters of 2 to 7; petals are small, white to pink, shorter than the sepals. Fruits are the typical raspberry: a hollow globe-shaped “cap”; but ripe, seedy drupelets are dark purplish black.

In the Landscape: This species is more often grown for its fruit than ornamentally. Its prickly, wild nature makes it best suited for a wild garden. Its bluish-whitish stems and arching habit are attractive, but its hooked prickles will grab or scratch anyone walking too close!

Phenology: Bloom time: May-June; Fruit ripens: Jul-Aug.

Phenology: Bloom time: May-June; Fruit ripens: Jul-Aug.

Propagation: Stratify seeds warm for 90 days then cold at 40º F (4º C) for 90 days. Blackcap Raspberry can be vegetatively propagated by cuttings, layering or division.

Use by People: The berries were eaten fresh or dried by natives. They were also used to make a purple dye. In fact, when grown commercially, the soft berries are more often used to make a dye, such as is used on meat packages, than for food. Many people, however, love the flavor and use them to make pies, jams, jellies, or syrups. Berry-pickers beware! — the berries will stain your hands and it is difficult to avoid being scratched by prickles! A tea, high in vitamin C can be made from the leaves. Young shoots can be peeled, eaten raw, or cooked like asparagus.

Use by Wildlife: The brambles rank at the very top of summer foods for wildlife, especially birds: grouse, pigeons, quail, grosbeaks, jays, robins, thrushes, towhees, waxwings, sparrows, to name just a few. The berries are also popular with raccoons, opossums, skunks, foxes, squirrels, chipmunks and other rodents. The leaves and stems are eaten extensively by deer and rabbits. Bear, beaver and marmots eat fruit, bark and twigs. Flowers are usually pollinated by insects. These usually prickly plants make impenetrable thickets where small animals find secure cover.

Links:

USDA Plants Database

Consortium of Pacific Northwest Herbaria

WTU Herbarium Image Collection, Plants of Washington, Burke Museum

E-Flora BC, Electronic Atlas of the Flora of British Columbia

Jepson Eflora, University of California

Calphotos

Ladybird Johnson Wildflower Center

Virginia Tech ID Fact Sheet

Plants for a Future Database

Native American Ethnobotany, University of Michigan, Dearborn

American Red Raspberry

Rubus idaeus L. ssp. strigosus (Michx.) Focke

The species type, Red Raspberry, R. idaeus, is native to Europe and northern Asia. Idaeus is derived from Mt. Ida in Crete where Jupiter was hidden as an infant. American Red Raspberry, or Grayleaf Red Raspberry, also known as Rubus strigosus (strigosus means bristled), can be found throughout much of North America, excluding the southwestern United States. In our region, it is found in some parts of the Cascades. Many cultivated varieties and hybrids are available for growing luscious berries; red, yellow, black, or purple!

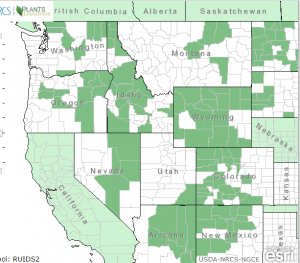

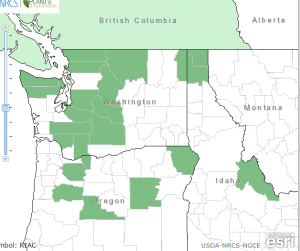

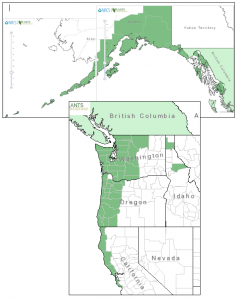

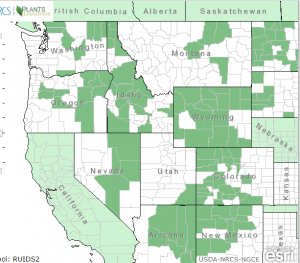

Distribution of American Red Raspberry

Links:

USDA Plants Database

Consortium of Pacific Northwest Herbaria

WTU Herbarium Image Collection, Plants of Washington, Burke Museum

E-Flora BC, Electronic Atlas of the Flora of British Columbia

Calphotos

Ladybird Johnson Wildflower Center

USDA Forest Service-Fire Effects Information System

Virginia Tech ID Fact Sheet

Native Plants Network, Propagation Protocol Database

Plants for a Future Database

Native American Ethnobotany, University of Michigan, Dearborn

Names: Stink Currant is also sometimes called Blue Currant, Stinking Black Currant or Californian Black Currant. All parts of this plant are sprinkled with yellow glands that emit a sweet-skunky odor—giving it its common name. Bracteosum refers to the 1-3 tiny bracteoles (small bracts) immediately under the flower. Currants and gooseberries belong to the genus Ribes (from the Arabic or Persian word ribas meaning acid-tasting).

Names: Stink Currant is also sometimes called Blue Currant, Stinking Black Currant or Californian Black Currant. All parts of this plant are sprinkled with yellow glands that emit a sweet-skunky odor—giving it its common name. Bracteosum refers to the 1-3 tiny bracteoles (small bracts) immediately under the flower. Currants and gooseberries belong to the genus Ribes (from the Arabic or Persian word ribas meaning acid-tasting).

Names: Other common names include Pink Winter Currant and Blood Currant. Sanguineum means “blood-red;” referring to the color of the flowers; although the flowers are usually a rosy or pale pink. You may find plants with flowers ranging from white to a deep red. There are several named cultivated varieties with red, pink, two-tone or white flowers. Var. glutinosum, found along the coast of California and Oregon, has less hairy leaves. Currants and gooseberries belong to the genus Ribes (from the Arabic or Persian word ribas meaning acid-tasting).

Names: Other common names include Pink Winter Currant and Blood Currant. Sanguineum means “blood-red;” referring to the color of the flowers; although the flowers are usually a rosy or pale pink. You may find plants with flowers ranging from white to a deep red. There are several named cultivated varieties with red, pink, two-tone or white flowers. Var. glutinosum, found along the coast of California and Oregon, has less hairy leaves. Currants and gooseberries belong to the genus Ribes (from the Arabic or Persian word ribas meaning acid-tasting).

Diagnostic Characters: The arching stems of Salmonberry have golden-brown, shedding bark, similar to Pacific Ninebark. Salmonberry stems, although largely unarmed, can range from having scattered prickles to being very bristly. Smaller twigs zigzag slightly from node to node. Leaves have 3 sharply toothed leaflets, the lateral ones smaller and sometimes unequally lobed or divided. Five-petalled flowers are a striking pink to reddish-purple. The fruits are raspberry-like with a hollow core, ranging from yellow to orange-red.

Diagnostic Characters: The arching stems of Salmonberry have golden-brown, shedding bark, similar to Pacific Ninebark. Salmonberry stems, although largely unarmed, can range from having scattered prickles to being very bristly. Smaller twigs zigzag slightly from node to node. Leaves have 3 sharply toothed leaflets, the lateral ones smaller and sometimes unequally lobed or divided. Five-petalled flowers are a striking pink to reddish-purple. The fruits are raspberry-like with a hollow core, ranging from yellow to orange-red. Phenology: Bloom time: April-May. Fruit ripens: May-July.

Phenology: Bloom time: April-May. Fruit ripens: May-July.

Names: Thimbleberries have a hollow core, like raspberries, making the berries easy to fit on the tip of a finger like a thimble. Rubus is derived from ruber, a latin word for red. Although parviflorus means small-flowered, the flowers of this species are among the largest of any Rubus species; it may get its name from a comparison to white wild roses. This species may also be called Western Thimbleberry, Western Thimble Raspberry, or White-flowering Raspberry.

Names: Thimbleberries have a hollow core, like raspberries, making the berries easy to fit on the tip of a finger like a thimble. Rubus is derived from ruber, a latin word for red. Although parviflorus means small-flowered, the flowers of this species are among the largest of any Rubus species; it may get its name from a comparison to white wild roses. This species may also be called Western Thimbleberry, Western Thimble Raspberry, or White-flowering Raspberry.

Diagnostic Characters: Thimbleberry stems have no prickles, and gray, shedding bark. Leaves are large, lobed, like maple leaves and fuzzy on both sides. Flowers are white and large (about 4 cm); borne 3-7 in a terminal cluster. The fruit is an aggregate of small, red, hairy drupelets in the shape of a domed cap.

Diagnostic Characters: Thimbleberry stems have no prickles, and gray, shedding bark. Leaves are large, lobed, like maple leaves and fuzzy on both sides. Flowers are white and large (about 4 cm); borne 3-7 in a terminal cluster. The fruit is an aggregate of small, red, hairy drupelets in the shape of a domed cap.

Names: Blackcap Raspberry is also known as Whitebark Raspberry or simply Black Raspberry. Rubus, derived from ruber, a latin word for red, is the genus of plants generally called brambles. It includes blackberries, raspberries, dewberries, and cloudberries. Rasp- may have come from a 15th century word, raspis, which means “a fruit from which a drink could be made.” “Leucodermis means white skin, or “whitebark”—referring to the very glaucous (whitish bloom) on its stems.

Names: Blackcap Raspberry is also known as Whitebark Raspberry or simply Black Raspberry. Rubus, derived from ruber, a latin word for red, is the genus of plants generally called brambles. It includes blackberries, raspberries, dewberries, and cloudberries. Rasp- may have come from a 15th century word, raspis, which means “a fruit from which a drink could be made.” “Leucodermis means white skin, or “whitebark”—referring to the very glaucous (whitish bloom) on its stems.

Phenology: Bloom time: May-June; Fruit ripens: Jul-Aug.

Phenology: Bloom time: May-June; Fruit ripens: Jul-Aug.

Names: Nutkana is derived from Nootka; Nootka Sound is a waterway on the west coast of Vancouver Island in British Columbia that was named after the Nuu-Chah-Nulth tribe that live in the area. Nootka Rose is sometimes called Common, Wild, or Bristly Rose. There are four recognized varieties whose names suggest differences in bristling.

Names: Nutkana is derived from Nootka; Nootka Sound is a waterway on the west coast of Vancouver Island in British Columbia that was named after the Nuu-Chah-Nulth tribe that live in the area. Nootka Rose is sometimes called Common, Wild, or Bristly Rose. There are four recognized varieties whose names suggest differences in bristling.

In the landscape, Nootka Rose is beautiful but can be aggressive. It is great as a barrier plant, growing into an impenetrable thicket. Its fragrance fills the air in a seaside habitat. It is valuable for stabilizing banks, especially along streams.

In the landscape, Nootka Rose is beautiful but can be aggressive. It is great as a barrier plant, growing into an impenetrable thicket. Its fragrance fills the air in a seaside habitat. It is valuable for stabilizing banks, especially along streams. Use by People: Some natives ate the hips, raw or dried, or they boiled them to make a tea. The fruit tastes better after a frost. Care should be taken, however, there is a layer of hairs around the seeds (actually achenes); these hairs can cause irritation to the mouth and digestive tract. A decoction of the roots was used to treat sore throats or as an eyewash. The bark was used to make a tea to ease labor pains. Rose hips are sometimes used to make jams or jellies; they are rich in vitamins, such as A, C, & E.

Use by People: Some natives ate the hips, raw or dried, or they boiled them to make a tea. The fruit tastes better after a frost. Care should be taken, however, there is a layer of hairs around the seeds (actually achenes); these hairs can cause irritation to the mouth and digestive tract. A decoction of the roots was used to treat sore throats or as an eyewash. The bark was used to make a tea to ease labor pains. Rose hips are sometimes used to make jams or jellies; they are rich in vitamins, such as A, C, & E. Use by Wildlife:

Use by Wildlife:

Names: Baldhip Rose is also sometimes called Wood Rose, Dwarf or Little Wild Rose. Baldhip and Gymnocarpa (meaning naked fruit), refer to the fact that the flower sepals do not remain attached to the fruit.

Names: Baldhip Rose is also sometimes called Wood Rose, Dwarf or Little Wild Rose. Baldhip and Gymnocarpa (meaning naked fruit), refer to the fact that the flower sepals do not remain attached to the fruit.

Diagnostic characters: Bald-hip Rose is the easiest to distinguish from the other roses. Its stems have many soft, bristly, straight prickles. Leaves have 5-9 toothed leaflets. Flowers are small, pale pink to rose, fragrant, and are usually borne singly at the ends of branches. Fruits are small, red, pear-shaped, berry-like hips, with no sepals remaining attached.

Diagnostic characters: Bald-hip Rose is the easiest to distinguish from the other roses. Its stems have many soft, bristly, straight prickles. Leaves have 5-9 toothed leaflets. Flowers are small, pale pink to rose, fragrant, and are usually borne singly at the ends of branches. Fruits are small, red, pear-shaped, berry-like hips, with no sepals remaining attached.