Mountain Huckleberry The Heath Family– Ericaceae

Vaccinium membranaceum Douglas ex Torr.

(Vax-IH-nee-um mem-brain-uh-SEE-um)Names

Names: Mountain Huckleberry is also known as Thin-leaf Huckleberry (membranaceum = thin, like a membrane). It is also known as Big, Black, or Blue Huckleberry. It is Idaho’s State Fruit.

Names: Mountain Huckleberry is also known as Thin-leaf Huckleberry (membranaceum = thin, like a membrane). It is also known as Big, Black, or Blue Huckleberry. It is Idaho’s State Fruit.

Relationships: There are about 450 species of Vaccinium worldwide, about 40 in North America with about 15 in the Pacific Northwest. The genus Vaccinium includes Blueberries, Huckleberries, Cranberries, Lingonberries, Whortleberries, Bilberries and Cowberries.

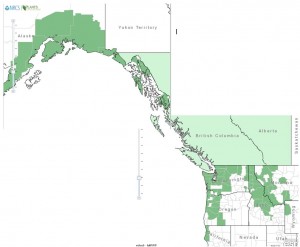

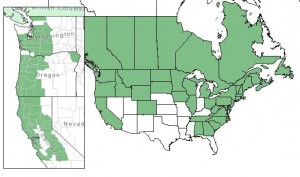

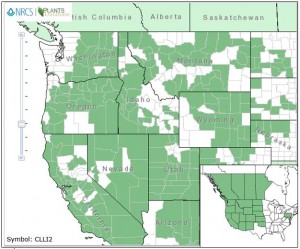

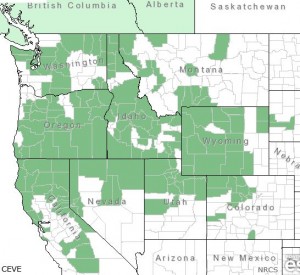

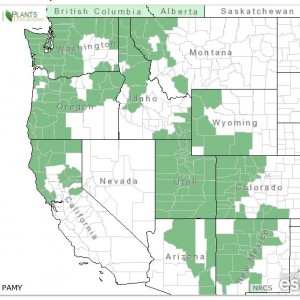

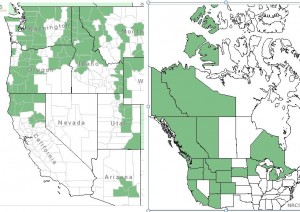

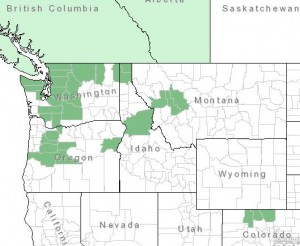

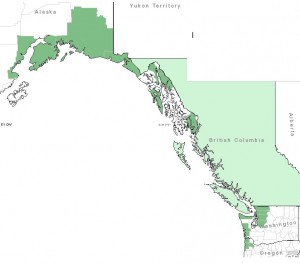

Distribution of Mountain Huckleberry from USDA Plants Database

Distribution: This species is found in the west from the Yukon Territory to Northern California, mostly in the Cascade Mountains; eastward through the Rocky Mountain States and Provinces; reaching to Minnesota, Upper Michigan, and Ontario, on the east side of Lake Superior.

Growth: Mountain Huckleberry grows from 1 to 4’ (30-150 cm).

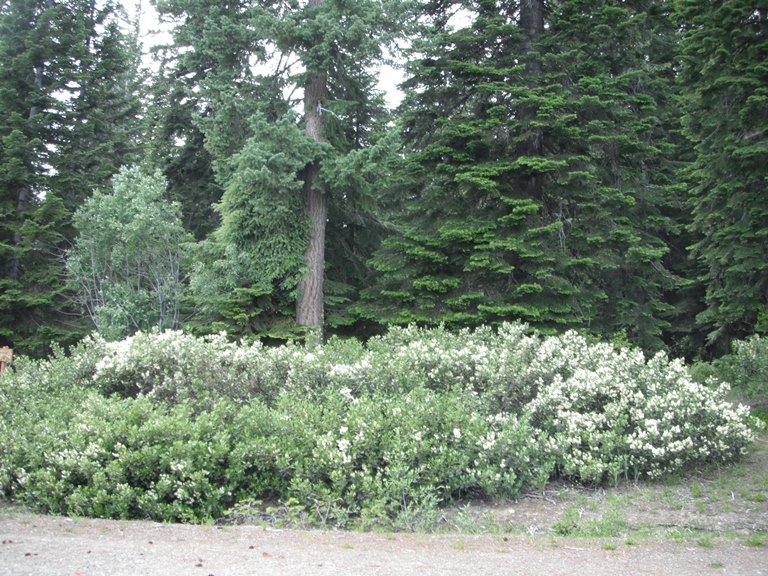

Habitat: It sometimes grows as an understory shrub in dry to moist coniferous forests but is most numerous on open subalpine slopes. In the Cascades, it is frequently found with Beargrass, Xerophyllum tenax. Roots may penetrate to a depth of 40” (100cm); rhizomes grow at between 3 to 12” (8-30cm) of the soil profile. After low to moderately severe fires, Mountain Huckleberry resprouts from the rhizomes. Fire exclusion reduces Black Huckleberry populations over time as they are overtaken by larger shrubs and trees. Wetland designation: FACU+, Facultative upland, it usually occurs in non-wetland but is sometimes found in wetlands

.

.

Diagnostic Characters: Mountain Huckleberry has thin leaves with finely toothed margins that are pointed at the tip. Flowers are urn-shaped and creamy-pink. The berries are purplish or reddish-black, without a waxy bloom.

Diagnostic Characters: Mountain Huckleberry has thin leaves with finely toothed margins that are pointed at the tip. Flowers are urn-shaped and creamy-pink. The berries are purplish or reddish-black, without a waxy bloom.

In the Landscape: This species is prized for its delicious berries. Its leaves turn a spectacular red to purple in the fall. Mountain Huckleberry does best when it has little competition from other plants and is ideal for a rock garden or on a slope with plenty of organic matter. Plant it together with its natural companion, Beargrass, to reproduce the look of a subalpine hillside. Soil moisture will affect the quality and quantity of berry production, although it still will fruit even after 4-6 months with no rain.

Phenology: Bloom time: Late spring to June. Fruit ripens: Mid-summer to late August.

Propagation: In nature, Mountain Huckleberry propagates mostly vegetatively by slow expansion via adventitious buds on its rhizomes. Although seed reproduction is reportedly rare in nature, seeds can be propagated with about a 42% germination rate. It is best to plant seeds as soon as they are ripe in a cold frame. Stored seed may require a 3 month stratification period. Cuttings are difficult but possible from half-ripe wood taken in August, with a heel. More success is likely with division of the rhizomes.

Use by People: The flavorful, juicy berries were collected by natives, eaten fresh or cooked, mashed and dried into cakes. Today, many families make special trips to the mountains to pick huckleberries. They go back to the same patch every year, unofficially claiming it as their own– hesitant to share the location with others. This is the species of huckleberry most commonly used in huckleberry Jams, syrups and other products marketed to tourists.

Use by Wildlife: Huckleberry flowers are pollinated by bees. Mountain Huckleberry is the dominant species of huckleberry consumed by Grizzly Bears and Black Bears; they eat the berries, leaves, stems and roots. Elk, moose and deer will also browse on the foliage. Small mammals, grouse and other birds also eat the berries as well as use the shrub as cover.

Links:

Consortium of Pacific Northwest Herbaria

WTU Herbarium Image Collection, Plants of Washington, Burke Museum

E-Flora BC, Electronic Atlas of the Flora of British Columbia

Jepson Eflora, University of California

Ladybird Johnson Wildflower Center

USDA Forest Service-Fire Effects Information System

Native Plants Network, Propagation Protocol Database

Native American Ethnobotany, University of Michigan, Dearborn

Vaccinium parvifolium Sm.

Vaccinium parvifolium Sm.

Cascade Azalea, Rhododendron albiflorum Hook. Also known as White-flowered (the meaning of albiflorum) Rhododendron, it has showy cup-shaped flowers. The upper surface of the leaves are covered with fine rusty hairs, the underside has white hairs only on the mid vein. Unfortunately, horticulturists have had very little success taming this subalpine gem in a cultivated garden. People continue to try; but for now only hikers can enjoy this beautiful rhododendron!

Cascade Azalea, Rhododendron albiflorum Hook. Also known as White-flowered (the meaning of albiflorum) Rhododendron, it has showy cup-shaped flowers. The upper surface of the leaves are covered with fine rusty hairs, the underside has white hairs only on the mid vein. Unfortunately, horticulturists have had very little success taming this subalpine gem in a cultivated garden. People continue to try; but for now only hikers can enjoy this beautiful rhododendron!

*False Azalea, Menziesia ferruginea Sm. False Azalea is also known as Fool’s Huckleberry, Mock Azalea, Rusty Menziesia, Rusty Leaf or other similar combinations. It is named after botanist and explorer, Archibald Menzies. Ferruginea (ferrous=iron) refers to the rusty-colored, glandular hairs on the leaves and twigs (although they are sometimes white). The bluish-green leaves are sticky with the mid-vein protruding slightly at the tip. They turn brilliant orange-red in the fall. The bell-shaped flowers are similar to huckleberry flowers, but are usually salmon-colored. It produces dry, 4-valved capsules instead of berries. Unlike, the previous two species, False Azalea is easier to grow and find in native plant nurseries. Many now lump it in with Rhododendrons, synonym: Rhododendron menziesii.

*False Azalea, Menziesia ferruginea Sm. False Azalea is also known as Fool’s Huckleberry, Mock Azalea, Rusty Menziesia, Rusty Leaf or other similar combinations. It is named after botanist and explorer, Archibald Menzies. Ferruginea (ferrous=iron) refers to the rusty-colored, glandular hairs on the leaves and twigs (although they are sometimes white). The bluish-green leaves are sticky with the mid-vein protruding slightly at the tip. They turn brilliant orange-red in the fall. The bell-shaped flowers are similar to huckleberry flowers, but are usually salmon-colored. It produces dry, 4-valved capsules instead of berries. Unlike, the previous two species, False Azalea is easier to grow and find in native plant nurseries. Many now lump it in with Rhododendrons, synonym: Rhododendron menziesii.