Pacific Yew The Yew Family–Taxaceae

(TAKS-us brev-i-FOAL-ee-uh)

Names: The Pacific Yew is also called the Western Yew or sometimes the Oregon Yew. Brevifolia means short leaves.

Relationships: There are about seven species of yew worldwide. Most are shrubs. The English species, T. baccata and the Japanese species, T. cuspidata have many cultivated varieties.

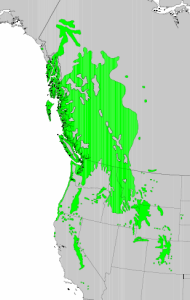

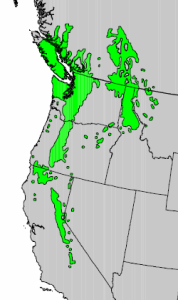

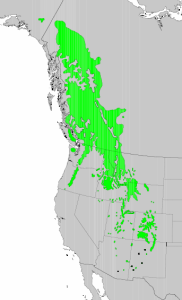

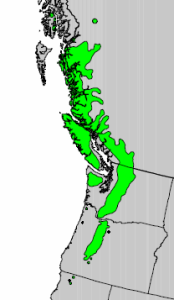

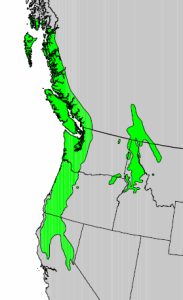

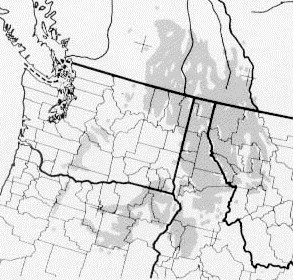

Distribution of Taxus brevifolia from USGS ( “Atlas of United States Trees” by Elbert L. Little, Jr. )

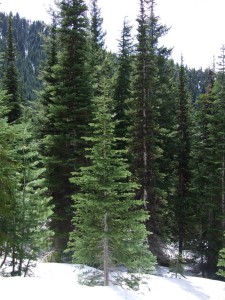

Distribution: The Pacific Yew is found from British Columbia to Northern California from the coast to the Cascades, on the western slope of the Sierra Nevadas and the western slope of the Rockies in B.C., Idaho and Montana. Rarely ever numerous, it is usually found as an understory tree in moist old growth forests growing beneath other larger trees such as Western Hemlock and Douglas Fir.

Growth: This rather scrubby looking tree grows slowly and usually only reaches 6 to 45 feet (2-15m). The largest are about 60 feet (18m).

Growth: This rather scrubby looking tree grows slowly and usually only reaches 6 to 45 feet (2-15m). The largest are about 60 feet (18m).

Wetland designation: FACU-, Facultative upland, it usually occurs in non-wetland but is only sometimes found in wetlands.

Diagnostic Characters: The needled foliage is similar in appearance to Douglas Fir, True Firs, and Hemlocks. The needles are arranged in 2 rows in flat sprays, similar to Grand Fir, but the needles are shorter, about an inch (2-3cm) long, coming to a point at the end. The twigs are green. Instead of a woody cone, female yew trees produce a bright red, berry-like, gelatinous cup called an aril. One bony seed is visible through the hole in the end of each aril. If you are lucky enough to find a mature yew, the bark is very shaggy looking with red to purplish shredded scales.

In the Landscape: Although many prefer its cultivated cousins, this somewhat homely, scraggly species may find a perfect home in a landscape for those that can appreciate its unconventional beauty. For those that have a small yard and cannot plant any of the larger native conifers, this little jewel may be the perfect choice!

In the Landscape: Although many prefer its cultivated cousins, this somewhat homely, scraggly species may find a perfect home in a landscape for those that can appreciate its unconventional beauty. For those that have a small yard and cannot plant any of the larger native conifers, this little jewel may be the perfect choice!

Phenology: Bloom Period: May to June, male and female on separate plants. Arils ripen in August to October; seeds are dispersed by birds and rodents, but will also just drop to the ground.

Propagation: Yew is easy to propagate from half-ripe terminal cuttings taken in summer. The seeds require warm stratification for 90 days, then a cold stratification at 40ºF (4ºC) for another 90 days. A germination rate of about 55% may be expected the 2nd spring.

Use by People: Yew wood was prized in both the old world and the new world for its strength and elasticity. It was used by natives to make many kinds of tools and weapons, particularly bows. Young native men would rub themselves with smooth yew sticks to give them strength. The wood is also ideal for carving and takes on a high polish. The fleshy seed coverings have been eaten in small quantities but should probably be avoided. The seeds are poisonous to humans!! Unfortunately loggers who were after the larger Douglas Fir, Hemlock and other trees of old growth forests did not have much regard for the Pacific Yew and many were destroyed in the process of harvesting the larger trees. The plight of the Pacific Yew gained attention in the 1980’s when it was discovered that its bark yielded the effective cancer-fighting drug, Taxol. Although there is a now synthetic alternative, the concern over the scarce tree, brought attention to the need for protecting our remaining old growth forests.

Use by People: Yew wood was prized in both the old world and the new world for its strength and elasticity. It was used by natives to make many kinds of tools and weapons, particularly bows. Young native men would rub themselves with smooth yew sticks to give them strength. The wood is also ideal for carving and takes on a high polish. The fleshy seed coverings have been eaten in small quantities but should probably be avoided. The seeds are poisonous to humans!! Unfortunately loggers who were after the larger Douglas Fir, Hemlock and other trees of old growth forests did not have much regard for the Pacific Yew and many were destroyed in the process of harvesting the larger trees. The plight of the Pacific Yew gained attention in the 1980’s when it was discovered that its bark yielded the effective cancer-fighting drug, Taxol. Although there is a now synthetic alternative, the concern over the scarce tree, brought attention to the need for protecting our remaining old growth forests.

Use by Wildlife: Birds eat the yew’s fleshy arils and disperse the seeds. The foliage is a winter browse for moose.

Links:

Consortium of Pacific Northwest Herbaria

WTU Herbarium Image Collection, Plants of Washington, Burke Museum

E-Flora BC, Electronic Atlas of the Flora of British Columbia

Jepson Manual, University of California

Ladybird Johnson Wildflower Center

USDA Forest Service-Fire Effects Information System

Native Plants Network, Propagation Protocol Database

Native American Ethnobotany, University of Michigan, Dearborn

National Register of Big Trees

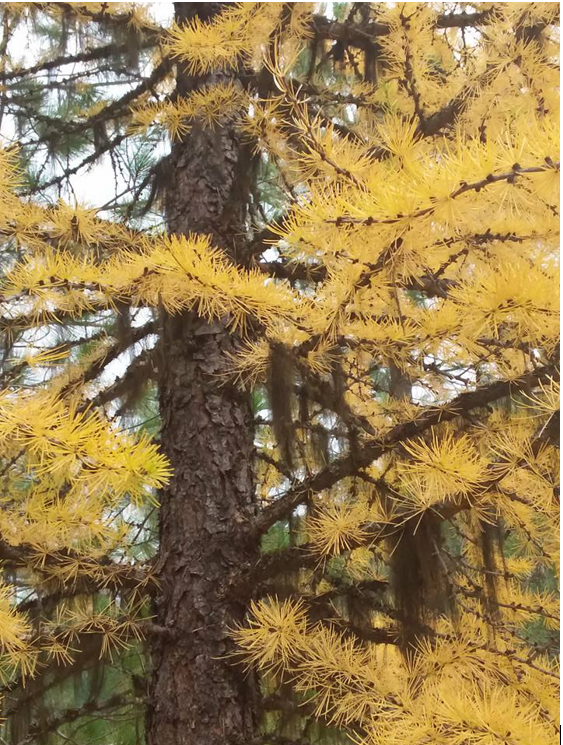

Unlike most conifers, Larches are deciduous; the needles turn a golden color in the fall before they are shed.

Unlike most conifers, Larches are deciduous; the needles turn a golden color in the fall before they are shed.

Habitat: It prefers moist, north or east facing mountain slopes but will also grow on dry, rocky soils. It is adapted to cool temperatures with moderate precipitation, often as snow. It is not tolerant of shade. Its thick bark and high canopy make it well adapted to fire.

Habitat: It prefers moist, north or east facing mountain slopes but will also grow on dry, rocky soils. It is adapted to cool temperatures with moderate precipitation, often as snow. It is not tolerant of shade. Its thick bark and high canopy make it well adapted to fire.