Cascara The Buckthorn Family–Rhamnaceae

Frangula purshiana (D.C.) Cooper

Frangula purshiana (D.C.) Cooper

(FRANG-yoo-luh pursh-ee-ANN-uh)

Names: Frangula is considered by some to be a subgenus of the Buckthorn genus, Rhamnus. More widely known as Rhamnus purshiana, this species is also well known by the common name, Cascara sagrada, meaning sacred bark in Spanish. The bark is used medicinally as a very strong laxative. Supposedly from Chinook Jargon, old-timers called it Chittam or Chitticum (“shit come”) bark. This species is also sometimes referred to as Cascara Buckthorn, or Pursh’s Buckthorn.

Relationships: There are about 100 species of Buckthorns worldwide throughout the northern hemisphere and in the southern hemisphere in parts of Africa and South America. There are about 7 or 8 species of Frangula in North America.

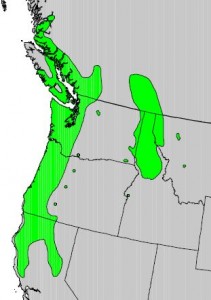

Distribution of Frangula purshiana from USGS ( “Atlas of United States Trees” by Elbert L. Little, Jr. )

Distribution: Cascara occurs from British Columbia through northern California, mostly on the west side of the Cascades, but is also found eastward to northern Idaho and northwestern Montana.

Growth: Cascara grows to 15-36 feet (5-12m). It grows smaller and shrubbier in the southern part of its range. Its ecological habitat varies greatly; from fairly dry, rocky, southern aspects to somewhat shady areas, with rich humusy soils, bordering swamps or slow-moving streams. Wetland designation: FAC-, Facultative, it is equally likely to occur in wetlands or non-wetlands.

Diagnostic Characters: Cascara leaves are distinctive, similar to dogwood, but are alternately arranged. They are dark, glossy green, elliptical to oblong, with furrowed, parallel veins. The flowers are greenish-yellow in umbrella-shaped clusters. The fruits ripen to a purplish-black. The bitter bark is a smooth, silver gray.

Diagnostic Characters: Cascara leaves are distinctive, similar to dogwood, but are alternately arranged. They are dark, glossy green, elliptical to oblong, with furrowed, parallel veins. The flowers are greenish-yellow in umbrella-shaped clusters. The fruits ripen to a purplish-black. The bitter bark is a smooth, silver gray.

In the Landscape: Attractive in all seasons, Cascara’s leaves are bright green in spring, turning dark and glossy in the summer. Yellow fall foliage is shed to reveal a picturesque branching pattern in winter. Cascara, however, does not adapt well to urban settings and is better in a woodland park or garden.

Phenology: Bloom Period: May-June. Fruits ripen August-September.

Propagation: Seeds are best sown in fall, 1 inch deep. Stored seed requires 1-3 months of cold stratification. Cuttings may be taken in late summer or fall of half-ripe to mature wood of the current year’s growth.

Use by People: As has already been mentioned, natives used Cascara bark tea as a laxative. It was introduced to modern medicine in 1877, and is still used in modern pharmaceuticals. Natives also used it on sores and swellings. The berries were eaten fresh in July and August. The bark and berries have also been used to make a yellow or green dye.

Use by Wildlife: Deer or other mammals may browse Cascara occasionally. The berries are attractive to birds, small mammals and raccoons. They are especially favored by Pileated Woodpeckers.

Links:

Consortium of Pacific Northwest Herbaria

WTU Herbarium Image Collection, Plants of Washington, Burke Museum

E-Flora BC, Electronic Atlas of the Flora of British Columbia

Jepson Eflora, University of California

Ladybird Johnson Wildflower Center

USDA Forest Service-Fire Effects Information System

Native Plants Network, Propagation Protocol Database

Native American Ethnobotany, University of Michigan, Dearborn