Red-Twig Dogwood Cornaceae-Dogwood Family

Cornus sericea L.

(KOR-nus sir-IH-see-uh)

Red Twig Dogwood variety with a Yellow Twig Dogwood (Cornus sericea ‘Flaviramea’) in the background.

Names: Cornus sericea is synonymous with Cornus stolonifera. Cornus means horn or antler, or “the ornamental knobs at the end of the cylinder on which ancient manuscripts were rolled”—which may refer to the hard wood or the knobby-looking inflorescence of some dogwoods. Sericea means covered with fine, silky hairs, which are found on the undersides of the leaves, especially on the veins; or on the young branches. Stolonifera means “bearing stolons (running stems),” due to this shrub’s habit of spreading by the layering of prostrate stems. It is often called Red-osier Dogwood; other common names include: Red-stemmed, Rose, Silky, American, California, Creek, Western, or Poison Dogwood, Squawbush, Shoemack, Waxberry Cornel, Red-osier Cornel, Red-stemmed Cornel, Red Willow, Red Brush, Red Rood, Harts Rouges, Gutter Tree and Dogberry Tree. “Osier” is a name for willows whose branches are used for making baskets or wicker furniture.

Relationships: There are about 100 dogwood species worldwide found primarily in temperate regions. Three Dogwood trees and a couple of shrub species are found in the eastern or Midwestern United States. In our region, we also have the Pacific Dogwood tree, and a groundcover, Bunchberry, Cornus canadensis.

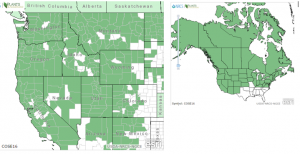

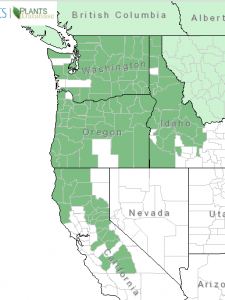

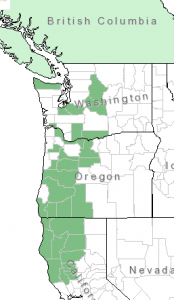

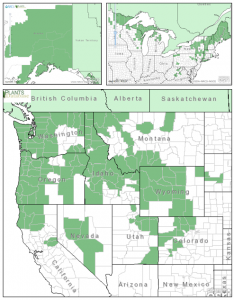

Distribution of Red Twig Dogwood from USDA Plants Database

Distribution: Red-Twig Dogwood is found throughout most of northern and western North America, extending into Mexico in the west; but barely into Kentucky and Virginia in the east. The variety found west of the Cascades, C. s. occidentalis, tends to be more hairy. Red-Twig Dogwood is extremely variable; many cultivated varieties are available varying in stem color, size, and leaf variegation. Notable varieties include ‘Flaviramea,” a yellow-twig form; “Isanti,” a compact form (to 5’) with bright red stems; ‘Kelseyi,’ a dwarf form to 1.5’; and ‘Silver and Gold’ with yellow branches and creamy-edged foliage.

Growth: The species grows 6-18 feet (2-6m) tall, often reaching tree stature in our area.

Habitat: It usually grows in moist soil, especially along streams and lakesides, in wet meadows, open forests and along forest edges. Wetland designation: FACW, It usually occurs in wetlands, but is occasionally found in non-wetlands.

Diagnostic characters: Leaves are opposite, oval-shaped, pointed at the tip with the typical dogwood veining pattern; 5-7 secondary veins arise at the midvein, and run parallel to each other out to the margin, converging at the tip. White threads run through the veins. Flowers are small, white to greenish in dense, flat-topped clusters (bracts not large and showy as in other dogwoods). Fruits are white, sometimes blue-tinged with a somewhat flattened stone pit. Stems are often bright red, especially in winter, but also can be greenish, or yellow.

Diagnostic characters: Leaves are opposite, oval-shaped, pointed at the tip with the typical dogwood veining pattern; 5-7 secondary veins arise at the midvein, and run parallel to each other out to the margin, converging at the tip. White threads run through the veins. Flowers are small, white to greenish in dense, flat-topped clusters (bracts not large and showy as in other dogwoods). Fruits are white, sometimes blue-tinged with a somewhat flattened stone pit. Stems are often bright red, especially in winter, but also can be greenish, or yellow.

In the Landscape: Red-Twig Dogwood is most often grown for its striking red twigs for winter interest. In fall, its white berries are a striking contrast against its brilliant red fall foliage. It is especially useful for planting in Rain Gardens, around water retention swales, and for stabilizing streambanks, especially where seasonal flooding is a concern. It is good for a quick space-filler and can be used as an effective screen in the summer. This species also shows promise for being useful in reclaiming mining sites with high saline tailings.

In the Landscape: Red-Twig Dogwood is most often grown for its striking red twigs for winter interest. In fall, its white berries are a striking contrast against its brilliant red fall foliage. It is especially useful for planting in Rain Gardens, around water retention swales, and for stabilizing streambanks, especially where seasonal flooding is a concern. It is good for a quick space-filler and can be used as an effective screen in the summer. This species also shows promise for being useful in reclaiming mining sites with high saline tailings.

Phenology: Bloom time: May-July; Fruit ripens: August-September.

Propagation: Cold stratify seeds at 40º F (4º C) for 60-120 days. Scarifying seeds or a warm stratification period for 60 days prior to cold stratification may increase germination rates. Red-Twig Dogwood is easily propagated from division, layering and cuttings taken in late summer.

Use by People: Some natives smoked the dried bark during ceremonies (hence the common name kinnikinnik which usually refers to Arctostaphylos uva-ursi). They also boiled it and used it medicinally for coughs, colds, fevers, and diarrhea. The sap was used on arrowheads to poison animals. The berries were eaten by some tribes, often mixed with Serviceberries. The bark was used for dye and the stems for basketry, fish traps, and arrows. The branches are attractive in floral arrangements.

Use by People: Some natives smoked the dried bark during ceremonies (hence the common name kinnikinnik which usually refers to Arctostaphylos uva-ursi). They also boiled it and used it medicinally for coughs, colds, fevers, and diarrhea. The sap was used on arrowheads to poison animals. The berries were eaten by some tribes, often mixed with Serviceberries. The bark was used for dye and the stems for basketry, fish traps, and arrows. The branches are attractive in floral arrangements.

Use by Wildlife: Red-twig Dogwood is an important browse for deer, elk, moose, Mountain Goats, and rabbits. Although not as desirable as other fruits, the berries often persist through winter, providing food when other fruits are gone. Mice, voles and other rodents eat the bark and the berries. Turkeys, pheasants, quail, and grouse eat the fruit & buds. Bears, ducks, and trout also eat the berries along with many songbirds, the primary agents of seed dispersal. Beavers use Red-twig Dogwood for food and to build dams and lodges. Red-Twig Dogwood provides cover and nesting habitat for small mammals and birds and along with other riparian species provides good mule deer fawning and fawn-rearing areas. Flowers are primarily pollinated by bees. This species is also a larval host of the Spring Azure Butterfly.

Links:

Consortium of Pacific Northwest Herbaria

WTU Herbarium Image Collection, Plants of Washington, Burke Museum

E-Flora BC, Electronic Atlas of the Flora of British Columbia

Jepson Eflora, University of California

Ladybird Johnson Wildflower Center

USDA Forest Service-Fire Effects Information System

Native Plants Network, Propagation Protocol Database

Native American Ethnobotany, University of Michigan, Dearborn

Names: Lewis’ Mock Orange is also known as Wild, Western, Pacific, Idaho or California Mock Orange. Presumably due to its growth habit, it is sometimes also called Syringa, the name for the unrelated lilac genus. Philadelphus means “brotherly love;” named after Pharoah Ptolemy II Philadelphus. The common name, Mock Orange comes from the similarity of the flowers, in fragrance and appearance, to citrus flowers. Lewis’ Mock Orange was discovered by Meriwether Lewis in 1806.

Names: Lewis’ Mock Orange is also known as Wild, Western, Pacific, Idaho or California Mock Orange. Presumably due to its growth habit, it is sometimes also called Syringa, the name for the unrelated lilac genus. Philadelphus means “brotherly love;” named after Pharoah Ptolemy II Philadelphus. The common name, Mock Orange comes from the similarity of the flowers, in fragrance and appearance, to citrus flowers. Lewis’ Mock Orange was discovered by Meriwether Lewis in 1806.

Names: Lacustre means “found in lakes.” Black Swamp Gooseberry has many common names including: Black Swamp Currant; Swamp Black Gooseberry (or Currant); Prickly Black Gooseberry (or Currant); Black Prickly Currant; Bristly Black Gooseberry (or Currant); Black Bristly Currant; Spiny Swamp Gooseberry (or Currant); Swamp Goose Current; Marsh Currant; Lake Gooseberry; and Lowland Gooseberry.

Names: Lacustre means “found in lakes.” Black Swamp Gooseberry has many common names including: Black Swamp Currant; Swamp Black Gooseberry (or Currant); Prickly Black Gooseberry (or Currant); Black Prickly Currant; Bristly Black Gooseberry (or Currant); Black Bristly Currant; Spiny Swamp Gooseberry (or Currant); Swamp Goose Current; Marsh Currant; Lake Gooseberry; and Lowland Gooseberry.

Diagnostic Characters: Stems are erect in sun, spreading or trailing in shade; covered with many golden, bristly, prickles with spines (usually smaller than on R.divaricatum) at the leaf nodes. Leaves are small with 5 deeply indented lobes. Small flowers, 5-15, are borne on pendulous, drooping clusters. Calyces range to a pale yellowish green to a mahogany-red; petals are pinkish. Fruits are dark-purple with glandular hairs.

Diagnostic Characters: Stems are erect in sun, spreading or trailing in shade; covered with many golden, bristly, prickles with spines (usually smaller than on R.divaricatum) at the leaf nodes. Leaves are small with 5 deeply indented lobes. Small flowers, 5-15, are borne on pendulous, drooping clusters. Calyces range to a pale yellowish green to a mahogany-red; petals are pinkish. Fruits are dark-purple with glandular hairs. Use by People: The berries were eaten fresh by most of the native tribes of the northwest, although some considered them poisonous. The fruit is said to have an “agreeable flavor,” tart and very juicy, but when crushed it has an offensive odor. The fruit can be made into sauces, jams or preserves. This prickly shrub was thought to have protective qualities to ward off evil and was used to discourage snakes. A tea made from the bark was used drunk during childbirth or as an eyewash for sore eyes. The roots were used to make rope and reef nets.

Use by People: The berries were eaten fresh by most of the native tribes of the northwest, although some considered them poisonous. The fruit is said to have an “agreeable flavor,” tart and very juicy, but when crushed it has an offensive odor. The fruit can be made into sauces, jams or preserves. This prickly shrub was thought to have protective qualities to ward off evil and was used to discourage snakes. A tea made from the bark was used drunk during childbirth or as an eyewash for sore eyes. The roots were used to make rope and reef nets.