Western Sword Fern The Wood Fern Family–Dryopteridaceae

Polystichum munitum (Kaulf.) C. Presl

(Pol-ee-STIK-um mew-NEE-tum)

Names: Polystichum means many rows, referring to the arrangement of the spore cases on the undersides of the fronds. Munitum means armed with teeth, referring to its toothed fronds. Western Sword Fern is also known as Sword Holly Fern, Giant Holly Fern, Christmas Fern, Pineland Sword Fern, or Chamisso’s Shield Fern.

Names: Polystichum means many rows, referring to the arrangement of the spore cases on the undersides of the fronds. Munitum means armed with teeth, referring to its toothed fronds. Western Sword Fern is also known as Sword Holly Fern, Giant Holly Fern, Christmas Fern, Pineland Sword Fern, or Chamisso’s Shield Fern.

Relationships: There are about 260 species of Polystichum worldwide with about 16 native to North America; and about 10 native to the Pacific Northwest.

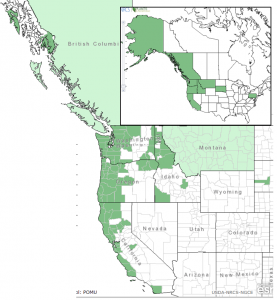

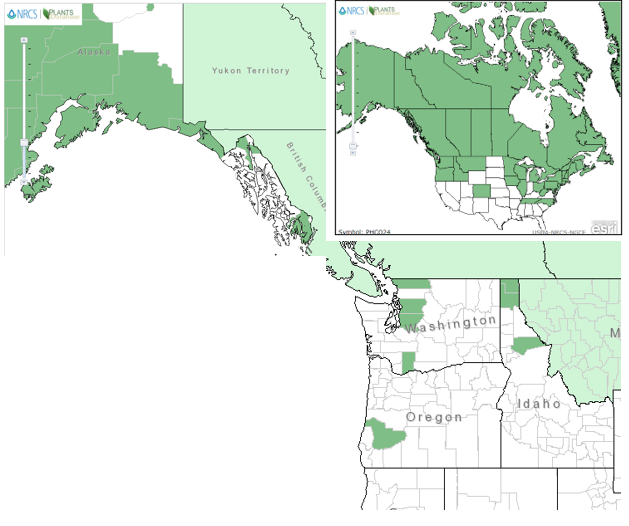

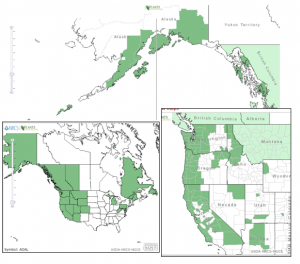

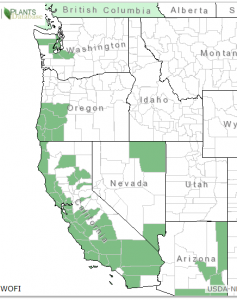

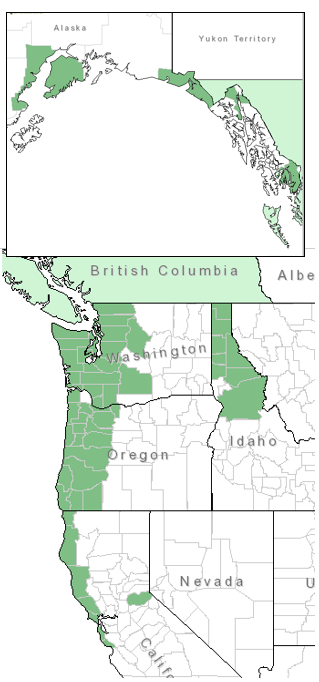

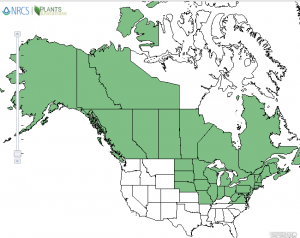

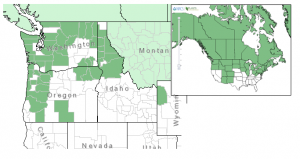

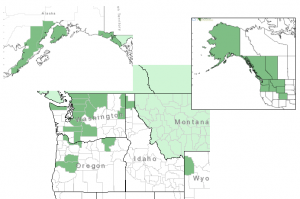

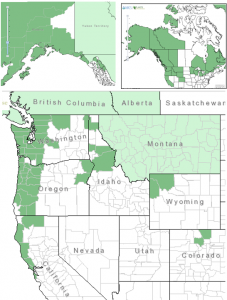

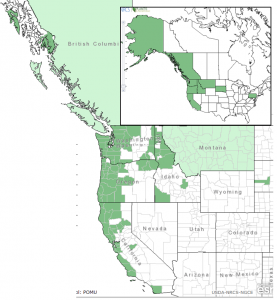

Distribution of Western Sword Fern from USDA Plants Database

Distribution: Western Sword Fern is found from southeast Alaska to the central California coast, mostly on the west of the Cascades; eastward to northern Idaho into northwest Montana. Disjunct populations have been found in South Dakota and on Guadalupe Island off Baja California.

Growth: Western Sword Fern grows up to 4.5 feet (1.5m) tall.

Habitat: It is usually found in moist forests, but it is probably the most adaptable of all our ferns and can take a bit more sun than other ferns and some dry periods. Wetland designation: FACU, it usually occurs in non-wetlands but occasionally is found in wetlands.

Sword Fern is very common in the understory in our westside forests.

Diagnostic Characters: Large, erect fronds form from a crown of scaly rhizomes. Fronds are once-pinnate with alternate pointed, sharp-toothed leaflets; each leaflet with a small lobe pointed forward at the base. Sori (spore cases) are large and round arranged in two rows on the undersides of the fronds halfway between the midvein and margins.

In the Landscape: Western Sword Fern is the most widespread and versatile of all our native ferns. Although at home in woodlands, it often adapts to drier, sunnier sites in landscapes. Its tall arching fronds are most impressive planted in drifts in a woodland garden. When grown in the sun, the fronds are dwarfed and more erect; and have pinnae (leaflets) that are crisped and crowded so that they overlap and appear overlapping. Young ferns are also more frilly-looking.

Phenology: Fronds partially unroll their “fiddleheads” by late May; by late July the spores are near maturity.

Phenology: Fronds partially unroll their “fiddleheads” by late May; by late July the spores are near maturity.

Sword Fern Fiddleheads.

Use by natives: The roots/rhizomes were generally viewed by natives as a famine food. (This plant probably should only be consumed in small quantities, if at all, due to possible presence of carcinogens or other toxins.) The rhizomes were peeled and then boiled or baked in a pit on hot rocks covered with fronds. The fronds were used frequently for lining baking pits and storage baskets; and were spread on drying racks to prevent berries from sticking. They were variously used for placemats, floor coverings, bedding; and for games, dancing skirts and other decorations. They are frequently used today in flower arrangements.

Use by natives: The roots/rhizomes were generally viewed by natives as a famine food. (This plant probably should only be consumed in small quantities, if at all, due to possible presence of carcinogens or other toxins.) The rhizomes were peeled and then boiled or baked in a pit on hot rocks covered with fronds. The fronds were used frequently for lining baking pits and storage baskets; and were spread on drying racks to prevent berries from sticking. They were variously used for placemats, floor coverings, bedding; and for games, dancing skirts and other decorations. They are frequently used today in flower arrangements.

Use by wildlife: Western Sword Fern is browsed by deer, elk, Black Bear and Mountain Beaver; frequently eaten by Roosevelt Elk on the Olympic Peninsula. The fronds may be used as nesting material for rodents.

Western Sword Fern outcrosses frequently and hybrids have been identified from crosses with Anderson’s Holly Fern (P. andersonii), Mountain Holly Fern, (P. scopulinum) California Sword Fern (P. californicum), Shasta Fern (P. lemmonii), and Narrowleaf Sword Fern, (P. imbricans)

Links:

USDA Plants Database

Consortium of Pacific Northwest Herbaria

WTU Herbarium Image Collection, Plants of Washington, Burke Museum

E-Flora BC, Electronic Atlas of the Flora of British Columbia

Jepson Eflora, University of California

Calphotos

Ladybird Johnson Wildflower Center

USDA Forest Service-Fire Effects Information System

Hardy Fern Library

Native Plants Network, Propagation Protocol Database

Plants for a Future Database

Native American Ethnobotany, University of Michigan, Dearborn

Other Polystichum sp., native to the Pacific Northwest:

Narrowleaf Sword Fern, P. imbricans is similar to Western Sword Fern and once was classified as a variety of P. munitum. It is smaller (20-60cm) with overlapping, somewhat infolded leaflets and only scarcely scaly stipes (petioles). It is a better choice for a sunny spot.

Anderson’s Holly Fern, P. andersonii is much rarer; found in deep woods in the mountains. Fronds grow to 1 meter. It has a conspicuously chaffy fiddlehead and leaf stalk. Pinnae are deeply cut making it appear doubly pinnate. Bulblets form at the base of pinnae near the tip and may grow into a new plant when the frond touches the ground!

Anderson’s Holly Fern

Braun’s Holly Fern, P. braunii, is big (to 1m) and has twice pinnate leaves with no basal lobes. It grows in moist woodlands. (Native to British Columbia, southern Alaska, the Idaho panhandle—Listed as threatened or endangered in several eastern U.S. states).

California Sword Fern, P. californicum, has finely toothed leaflets rather than the prominently toothed leaflets in Western Sword Fern; each tooth is short, ending abruptly. It will grow in a variety of habitats from moist, shaded woods to open slopes, and dry, rocky terrain. It is rare in Washington & Oregon, listed as sensitive in Washington, only found in or near the Cascades in Pierce & Thurston counties).

Kruckeberg’s Holly Fern, P. kruckebergii is believed to be a fertile hybrid of P. lonchitis & P. lemmonii. It is found sporadically in the Cascades, Sierras, & Rocky Mountains on rocks and cliffs and is considered rare or imperiled in Alaska, Montana, Idaho, California and B.C.; and “of concern” in Oregon. Fronds are about 10-25cm long. Short leaflets are oval to triangular, overlapping and twisted; with teeth tipped with spines. It is named after Dr. Arthur Kruckeberg, the well-known botanist and native plant gardener and enthusiast.

Kwakiutl Holly Fern, P. kwakiutlii is known only from the type specimen, collected at Alice Arm, British Columbia in 1934. It is presumed to be one of the diploid progenitors of P. andersonii. It also produced bulblets, but differs from P. andersonii in its completely divided pinnae (leaflets). Kwakiutl is a name applied to the native people in British Columbia on Vancouver Island and surrounding areas.

Lemmon’s or Shasta Holly Fern, P. lemmonii: Fronds are twice pinnate; pinnae have no spines and are overlapping and twisted, making it appear cylindrical. This species grows in serpentine rock crevices; and is found sporadically in the Cascades from B.C. to northern California. It is only known from one site in B.C. where it is listed as threatened.

Northern Holly Fern, P. lonchitis, grows in mountains, often in rock crevices, throughout much of the northern hemisphere. Lonchitis is from the Greek logch meaning spear, referring to its spear-shaped leaves. It is once pinnate with spiny leaflets; resembling a miniature Sword Fern. It is listed as endangered in New York; and is on a review list in California.

Mountain Holly Fern or Rock Sword Fern, P. scopulinum is also like a smaller Sword Fern but is shinier and more leathery with spiny-toothed leaves. It is nearly bipinnate with long hairs on the teeth of each leaflet. It is found in dry coniferous forest or more commonly on cliffs and talus slopes. It is more frequent east of the Cascades and the Rocky Mountains; it also grows in eastern Canada.

Alaska Holly Fern, P. setigerum, is presumed to a hybrid between P. munitum and P. braunii. Fronds are 2-pinnate about the middle, finely spiny-toothed. It is found in lowland coastal forests in Alaska and B.C. It may be able find a niche in a cool, moist woodland garden.

Names: Adiantum aleuticum is also known as A. pedatum var. aleuticum. Adiantum comes from the Greek, adiantos (unwetted), referring to how the leaves shed water. Aleuticum is derived from the Aleutian Islands. Pedatum means foot-like (usually a bird’s), referring to its fan-shaped fronds. Common names include: Five-finger Fern and Northern or Aleutian Maidenhair. The term Maidenhair may have been derived from the species A. capillus-veneris, (literally Venus’s hair), perhaps due to the dark, glossy hair-like leaf stalks. Ginkgo biloba is called “Maidenhair Tree” because the leaves resemble the pinnules of Maidenhair ferns.

Names: Adiantum aleuticum is also known as A. pedatum var. aleuticum. Adiantum comes from the Greek, adiantos (unwetted), referring to how the leaves shed water. Aleuticum is derived from the Aleutian Islands. Pedatum means foot-like (usually a bird’s), referring to its fan-shaped fronds. Common names include: Five-finger Fern and Northern or Aleutian Maidenhair. The term Maidenhair may have been derived from the species A. capillus-veneris, (literally Venus’s hair), perhaps due to the dark, glossy hair-like leaf stalks. Ginkgo biloba is called “Maidenhair Tree” because the leaves resemble the pinnules of Maidenhair ferns.

In the Landscape: Maidenhair Ferns are prized by gardeners for their delicate, airy fronds. Western Maidenhair is sure to evoke memories for avid hikers of enchanting waterfalls, where it grows on cliffs within reach of water spray. But the gardener should make sure this charmer gets planted in a shady place with plenty of moisture.

In the Landscape: Maidenhair Ferns are prized by gardeners for their delicate, airy fronds. Western Maidenhair is sure to evoke memories for avid hikers of enchanting waterfalls, where it grows on cliffs within reach of water spray. But the gardener should make sure this charmer gets planted in a shady place with plenty of moisture.

Names: Blechnum comes from a general Greek name for fern. Spicant means spiked referring to the erect fertile fronds. Other common names include: Hard Fern or Rough Spleenwort. It also has been known as Struthiopteris spicant.

Names: Blechnum comes from a general Greek name for fern. Spicant means spiked referring to the erect fertile fronds. Other common names include: Hard Fern or Rough Spleenwort. It also has been known as Struthiopteris spicant.

Names: Gymnocarpium means naked fruit because the spore cases are not covered with an indusium. The common name and specific epithet dryopteris refers to its similarity to the genus Dryopteris, (which literally means Oak (or Wood) Fern). Disjunctum refers to the separation of this species from G. dryopteris.

Names: Gymnocarpium means naked fruit because the spore cases are not covered with an indusium. The common name and specific epithet dryopteris refers to its similarity to the genus Dryopteris, (which literally means Oak (or Wood) Fern). Disjunctum refers to the separation of this species from G. dryopteris.

Names: Athyrium possibly comes from the Greek athyros, meaning doorless, referring to the late opening of the spore cases. Filix-femina means fern-lady, referring to its delicate fronds in comparison to the Male Fern, Dryopteris filix-mas. (Felix means happy or fruitful/fertile; a happy or fruitful lady could also be an appropriate name for this aggressive fern!)

Names: Athyrium possibly comes from the Greek athyros, meaning doorless, referring to the late opening of the spore cases. Filix-femina means fern-lady, referring to its delicate fronds in comparison to the Male Fern, Dryopteris filix-mas. (Felix means happy or fruitful/fertile; a happy or fruitful lady could also be an appropriate name for this aggressive fern!)

Diagnostic Characters: It has large, feathery 2-3 pinnate fronds, tapering at both ends, arising from a cluster of scaly rhizomes. Sori, or spore cases, are elongated and curved, oblong to horseshoe-shaped.

Diagnostic Characters: It has large, feathery 2-3 pinnate fronds, tapering at both ends, arising from a cluster of scaly rhizomes. Sori, or spore cases, are elongated and curved, oblong to horseshoe-shaped.

Names: Polystichum means many rows, referring to the arrangement of the spore cases on the undersides of the fronds. Munitum means armed with teeth, referring to its toothed fronds. Western Sword Fern is also known as Sword Holly Fern, Giant Holly Fern, Christmas Fern, Pineland Sword Fern, or Chamisso’s Shield Fern.

Names: Polystichum means many rows, referring to the arrangement of the spore cases on the undersides of the fronds. Munitum means armed with teeth, referring to its toothed fronds. Western Sword Fern is also known as Sword Holly Fern, Giant Holly Fern, Christmas Fern, Pineland Sword Fern, or Chamisso’s Shield Fern.

Phenology: Fronds partially unroll their “fiddleheads” by late May; by late July the spores are near maturity.

Phenology: Fronds partially unroll their “fiddleheads” by late May; by late July the spores are near maturity.

Use by natives: The roots/rhizomes were generally viewed by natives as a famine food. (This plant probably should only be consumed in small quantities, if at all, due to possible presence of carcinogens or other toxins.) The rhizomes were peeled and then boiled or baked in a pit on hot rocks covered with fronds. The fronds were used frequently for lining baking pits and storage baskets; and were spread on drying racks to prevent berries from sticking. They were variously used for placemats, floor coverings, bedding; and for games, dancing skirts and other decorations. They are frequently used today in flower arrangements.

Use by natives: The roots/rhizomes were generally viewed by natives as a famine food. (This plant probably should only be consumed in small quantities, if at all, due to possible presence of carcinogens or other toxins.) The rhizomes were peeled and then boiled or baked in a pit on hot rocks covered with fronds. The fronds were used frequently for lining baking pits and storage baskets; and were spread on drying racks to prevent berries from sticking. They were variously used for placemats, floor coverings, bedding; and for games, dancing skirts and other decorations. They are frequently used today in flower arrangements.