Douglas Spiraea The Rose Family–Rosaceae

Spiraea douglasii Hook.

(spy-REE-uh duh-GLASS-ee-i)

Names: The word Spiraea comes from a Greek plant that was commonly used for garlands. Douglas Spiraea is named after David Douglas. It is also commonly known as Hardhack, Steeplebush, or as Western, Pink or Rose Spiraea. There are two recognized varieties, var. douglasii, which has grayish wooly hairs on the undersides of its leaves; and var. menziesii, (sometimes known as S. menziesii) which has smooth or only slightly hairy leaves.

Names: The word Spiraea comes from a Greek plant that was commonly used for garlands. Douglas Spiraea is named after David Douglas. It is also commonly known as Hardhack, Steeplebush, or as Western, Pink or Rose Spiraea. There are two recognized varieties, var. douglasii, which has grayish wooly hairs on the undersides of its leaves; and var. menziesii, (sometimes known as S. menziesii) which has smooth or only slightly hairy leaves.

Relationships: Spiraeas are collectively known as Meadowsweets. There are about 80-100 species of spiraea in the temperate regions of the northern hemisphere-the majority in eastern Asia. Many are grown for ornamental landscaping and there are several cultivated varieties, mostly of the Japanese species.

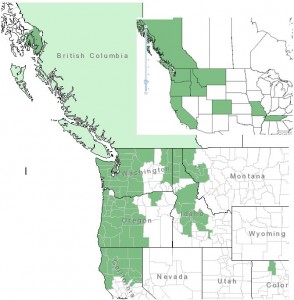

Distribution of Douglas Spiraea from USDA Plants Database

Distribution: Douglas Spiraea is native from southeast Alaska to northern California. Although it mostly occurs west of the Cascade Mountains, it is also found in eastern Washington, Idaho and western Montana. Douglas Spiraea has also been found growing in isolated counties of Colorado, Missouri, and Tennessee.

Growth: Spiraea douglasii grows 3-6 ft (1-2 m). It spreads by rhizomes, and is very aggressive, It often forms dense colonies and can quickly become the dominant species in a wetland habitat.

Habitat: Douglas Spiraea grows in open areas of wet meadows, bogs, streambanks, and lake margins. Labrador Tea, Ledum groenlandicum, is often a companion of Douglas Spiraea in bogs. It can withstand drier periods in areas that are only seasonally wet. Wetland designation: FACW, It usually occurs in wetlands, but is occasionally found in non-wetlands.

Habitat: Douglas Spiraea grows in open areas of wet meadows, bogs, streambanks, and lake margins. Labrador Tea, Ledum groenlandicum, is often a companion of Douglas Spiraea in bogs. It can withstand drier periods in areas that are only seasonally wet. Wetland designation: FACW, It usually occurs in wetlands, but is occasionally found in non-wetlands.

Diagnostic Characters: This species has oblong to oval leaves that are toothed above the middle. The undersides of the leaves are paler than the upper sides and are often covered with wooly, gray hairs. The flowers are purplish-pink clustered in an upright plume or “steeple.” The fruits are pod-like follicles (dry one-celled seed capsules, which split open one side).

In landscapes: Douglas Spiraea is especially useful in Rain Gardens, but care should be taken not to introduce it to an area where it is likely to overtake other desirable plants. It is a good choice for revegetation projects along streamsides. Its attractive purplish-pink flower plumes create a “sea of pink” in “Hardhack bogs” when in bloom.

In landscapes: Douglas Spiraea is especially useful in Rain Gardens, but care should be taken not to introduce it to an area where it is likely to overtake other desirable plants. It is a good choice for revegetation projects along streamsides. Its attractive purplish-pink flower plumes create a “sea of pink” in “Hardhack bogs” when in bloom.

Phenology: Bloom time: July-August; Fruit ripens: September-October.

Propagation: Douglas Spiraea is easy to start from seed. Fresh seed does not require stratification; dry seed may require 1-2 months cold stratification. Douglas Spiraea may also be propagated from stem or root cuttings, or division. After a fire or burial, it readily sprouts from the stem base and rhizomes. Douglas’ spirea showed extensive rhizome and adventitious root development in tephra after the 1980 Mt. St. Helen’s volcanic eruption.

Use by people: Some natives used Douglas Spiraea for spreading and cooking salmon and for making tools to collect dentalia shells for trade and decoration. The flowers are can be dried and used in floral arrangements.

Use by Wildlife: Douglas Spiraea is sometimes browsed by Black-tailed Deer. Flowers are pollinated by insects. In bogs, it provides cover for many water birds, such as Marsh Wrens, but alternatively may provide good hunting habitat for raptors.

Links:

Consortium of Pacific Northwest Herbaria

WTU Herbarium Image Collection, Plants of Washington, Burke Museum

E-Flora BC, Electronic Atlas of the Flora of British Columbia

Jepson Eflora, University of California

Ladybird Johnson Wildflower Center

USDA Forest Service-Fire Effects Information System

Native American Ethnobotany, University of Michigan, Dearborn

Names: Physo means bladder, carpus means fruit, referring to the inflated fruits. Capitatus means having a head, referring to its dense flower or fruit cluster. Ninebarks are so called because it was believed there are nine layers (or nine strips) of peeling bark on the stems. In the past it has been lumped in with P. opulifolia, Common Ninebark (an eastern species); along with this species, it was also known as Opulaster capitatus and Neillia opulifolia, Opulaster and opulifolia mean rich in flowers (asters) or in leaves (folia)–they may also refer to its similarity to Viburnum opulus. Because of its close association to spiraeas, it has also been known as Spiraea capitata. Western Ninebark is another common name.

Names: Physo means bladder, carpus means fruit, referring to the inflated fruits. Capitatus means having a head, referring to its dense flower or fruit cluster. Ninebarks are so called because it was believed there are nine layers (or nine strips) of peeling bark on the stems. In the past it has been lumped in with P. opulifolia, Common Ninebark (an eastern species); along with this species, it was also known as Opulaster capitatus and Neillia opulifolia, Opulaster and opulifolia mean rich in flowers (asters) or in leaves (folia)–they may also refer to its similarity to Viburnum opulus. Because of its close association to spiraeas, it has also been known as Spiraea capitata. Western Ninebark is another common name.

Propagation: Pacific Ninebark is easy to start from cuttings, or live stakes (direct planting of a cutting into its desired location). Seed propagation is possible, but much slower. Fall is the best time to sow the seeds, although many sources state that it does not require a stratification period.

Propagation: Pacific Ninebark is easy to start from cuttings, or live stakes (direct planting of a cutting into its desired location). Seed propagation is possible, but much slower. Fall is the best time to sow the seeds, although many sources state that it does not require a stratification period.

Diagnostic Characters: Its leaves are bright green in spring, lance-shaped, and entire (not toothed); and smell like cucumber when crushed. Small, five-lobed flowers are born in drooping clusters, usually appearing before the leaves. Each flower is white with a green calyx. They are said to have an unusual fragrance

Diagnostic Characters: Its leaves are bright green in spring, lance-shaped, and entire (not toothed); and smell like cucumber when crushed. Small, five-lobed flowers are born in drooping clusters, usually appearing before the leaves. Each flower is white with a green calyx. They are said to have an unusual fragrance  “something between watermelon rind and cat urine.” Others compare it to almonds. Some sources report that the female flowers have a pleasant fragrance, but the male flowers are unpleasant. The fruit are like small plums. Immature fruit is peach-colored, mature fruit is purple or bluish-black. Since Indian Plum is dioecious, you need to a have a female plant with nearby males for it to bear fruit. In natural populations, there are usually more males than females, due to a higher mortality of females. Males often flower at an earlier age than females; females have a slower growth rate.

“something between watermelon rind and cat urine.” Others compare it to almonds. Some sources report that the female flowers have a pleasant fragrance, but the male flowers are unpleasant. The fruit are like small plums. Immature fruit is peach-colored, mature fruit is purple or bluish-black. Since Indian Plum is dioecious, you need to a have a female plant with nearby males for it to bear fruit. In natural populations, there are usually more males than females, due to a higher mortality of females. Males often flower at an earlier age than females; females have a slower growth rate.