Noble Fir The Pine Family–Pinaceae

(Ay-beez prah-SIR-uh or pro-KAY-ruh)

Names: The name “procera” means “tall.” Noble Fir lives up to both its names, being both tall and noble! It is the tallest of all true firs.

Relationships: There are about 40 species of true firs in the world, 9 in North America. We have 4 in our region but only the Grand Fir, Abies grandis, is common in lower elevations.

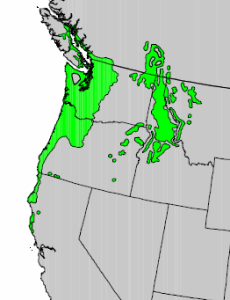

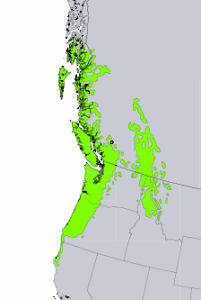

Distribution: Noble Fir is found in southwest Washington, Oregon and northern California, mostly in the Cascade Mountains with some isolated populations in the coastal mountains of Oregon and the Willapa Hills of southwest Washington. Shasta Fir, Abies x shastensis, is a common hybrid of Noble Fir and California Red Fir, A. magnifica; found in southern Oregon and California.

Growth: One of the tallest known living trees, near Randle, Washington, was 278 feet (85m) tall but has been in decline since the area surrounding it was clear-cut in the 1960’s. Currently, it sits at the edge of a clear-cut and, having lost its top 50 feet (15m), is now only 227’ feet (69m) tall. Many of the tallest, including historical trees that have reached 325 feet, grow (or once grew) near Mt. St. Helens. Noble Fir typically reaches 135 to 210 feet (40-65m) and lives about 300-400 years.

Habitat: Noble Fir is often a pioneer tree on middle to upper elevation sites, establishing itself quickly after a disturbance. It can grow quickly and can even surpass Douglas Fir. It is, however, shade intolerant and eventually gives way to Pacific Silver Fir, Abies amabilis, or Western Hemlock. Its bluish-green needles give a forest of Noble Fir a much different appearance than one of Douglas Fir. Much of the blast zone on the way to Johnston Ridge near Mt. St.Helen’s was replanted with Noble Fir (see feature photo at top of page). It was planted at much lower elevations than normal due to the vast areas of land that were being replanted after the eruption, (Weyerhaeuser Co. planted 45,000 acres!) and to the fact that Douglas Fir seedlings were consequently in limited quantity.

Habitat: Noble Fir is often a pioneer tree on middle to upper elevation sites, establishing itself quickly after a disturbance. It can grow quickly and can even surpass Douglas Fir. It is, however, shade intolerant and eventually gives way to Pacific Silver Fir, Abies amabilis, or Western Hemlock. Its bluish-green needles give a forest of Noble Fir a much different appearance than one of Douglas Fir. Much of the blast zone on the way to Johnston Ridge near Mt. St.Helen’s was replanted with Noble Fir (see feature photo at top of page). It was planted at much lower elevations than normal due to the vast areas of land that were being replanted after the eruption, (Weyerhaeuser Co. planted 45,000 acres!) and to the fact that Douglas Fir seedlings were consequently in limited quantity.

Diagnostic Characters: All firs are easily recognized by the smooth bark on young twigs and small, round leaf scars left by dropped needles. Older branches may be covered with resin blisters. Cones are borne upright in the tops of the trees. At maturity, the cones shed their scales while still on the tree; therefore it is rare to ever see an intact fir cone on the ground. A favorite Christmas tree, Noble Fir is easily recognized by upward curving needles that grow on opposite sides of a branch. Ornaments hang nicely from its open, symmetrically spaced branches.

In the Landscape: It makes a beautiful specimen tree in the landscape.

Phenology: Bloom Period: May to Early July. Cones mature in mid-August; seed dispersal begins the end of September to the beginning of October.

Propagation: Stratify seed at 40ºF (4ºC) for 28 days. Fresh seed is best but seeds may be stored up to 5 years. Germination rate is often poor.

Use by people: The wood of Noble Fir is the strongest of the true firs and is suitable for light construction and pulping.

Use by wildlife: Firs are useful to many animals for cover and nesting sites. Grouse eat the needles. Deer and elk eat the foliage and twigs in the winter. Birds, chipmunks and squirrels eat the seeds.

Care of Live Christmas Trees It is best to keep live Christmas trees outside. If you do bring one inside, try to limit the time kept inside to less than a week to prevent it from “breaking dormancy.” If a tree has been kept inside too long it will need to be kept in a cool, well-lit room until spring or when temperatures are less frigid. Keep the tree watered—do not allow it to dry out! Afterwards it may be planted at anytime! Loosen the root ball and/or prune circling roots. Keep watered in the summer until well established.–See Selecting a Christmas Tree on my sister website, habitathorticulturepnw.com !

Links:

Consortium of Pacific Northwest Herbaria

WTU Herbarium Image Collection, Plants of Washington, Burke Museum

Jepson Manual, University of California

Ladybird Johnson Wildflower Center

USDA Forest Service-Fire Effects Information System

Native Plants Network, Propagation Protocol Database

Native American Ethnobotany, University of Michigan, Dearborn