Several Evergreen Ericaceous Plants found mostly in wetlands:

Labrador Tea, Ledum* groenlandicum Oeder OBL

Labrador Tea is found throughout the northern latitudes, including Greenland as its name suggests. It has white flowers. The undersides of older leaves are covered with a rusty brown-colored fuzz. Natives and European settlers and traders used the leaves for tea, both as a beverage and medicinally. It should be consumed in moderation and not be confused with Trapper’s Tea, Bog Laurel, or Bog Rosemary which all lack brown fuzz and are toxic.

The undersides of older Labrador Tea leaves are covered with rusty-brown fuzz. (Younger leaves may have whitish fuzz.)

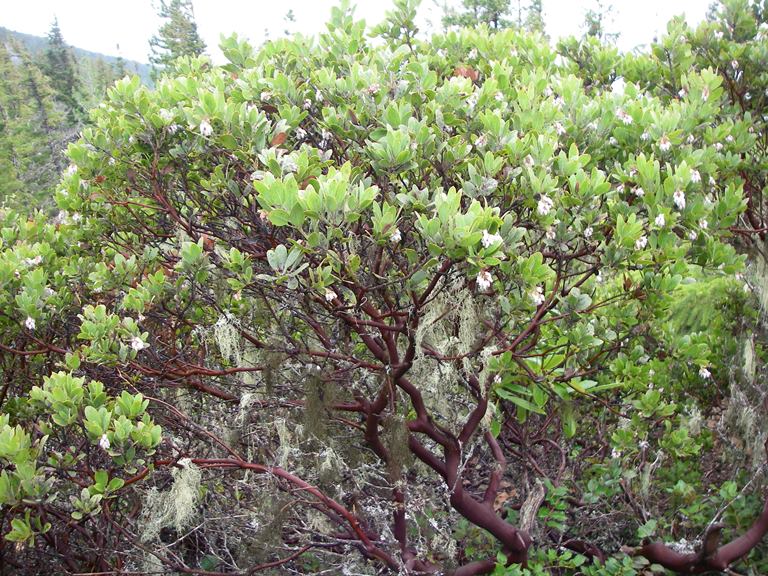

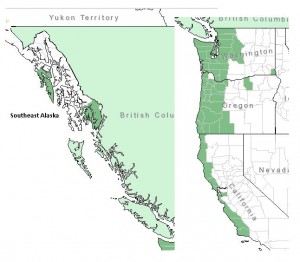

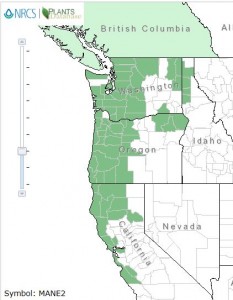

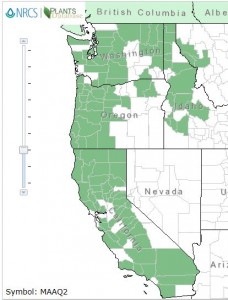

Trapper’s Tea, Ledum* glandulosum Nutt. FACW+

Trapper’s Tea is also known as Western Labrador Tea. It is similar to Labrador Tea but the leaves have whitish hairy undersides. It is more common east of the Cascade crest in Washington and in Oregon and California. Although it is known to be toxic, some interior tribes drank a tea made from the leaves of this plant.

*Many now place Ledum in the larger genus Rhododendron.

Alpine Laurel, Kalmia microphylla (Hook.) A. Heller FACW+

Alpine Laurel is also known as Western Bog Laurel, K. polifolia. It is native to western North America. Its small, attractive, rose pink flowers are borne in a truss. This small shrub is sometimes grown in gardens but is somewhat difficult to keep alive.

Bog Rosemary, Andromeda polifolia L. OBL

Bog Rosemary is also found throughout the northern latitudes. With its small, pinkish urn-shaped flowers, this small shrub has long been prized as a garden ornamental. I have never seen it live for long in the landscape—it needs to be planted in an appropriate location with plenty of moisture. In nature, Bog Rosemary grows on little moss hummocks surrounded by swamp. Similarly, in Greek mythology, Andromeda was a beautiful princess that was chained naked to a rock in the midst of the sea, as a sacrifice to a sea monster. The Greek hero, Perseus rescued her and subsequently married her.

Bog Cranberry, Vaccinium oxycoccus L. OBL

Bog Cranberry is another bog plant found throughout the northern latitudes. It is also known as Small Cranberry. Cranberries are sometimes placed in their own genus, Oxycoccus (oxy: acid; coccus: round berry). Bog Cranberry is a low, creeping shrub with small pink, nodding flowers like miniature shooting stars. The fruits are pink to dark red, smaller than the commercially grown V. macrocarpon. Natives ate the tart berries fresh or cooked; or stored them in moss or dried into cakes for later use.

Alpine Heather-like Plants

We have four mountain heathers almost exclusively found in alpine or subalpine parkland. They are White Mountain Heather, Cassiope mertensiana, Alaska Bell heather, Harrimanella stelleriana, Pink Mountain Heather, Phyllodoce empetriformis, and Yellow Mountain Heather, P. glanduliflora. All are very difficult to keep alive in lower elevation gardens. It is perhaps better to find cultivated varieties of similar species to use in your garden and leave these gems in their natural environment.

Two other alpine heather-like plants can be adapted to the garden. The Alpine Azalea, Loiseleuria procumbens has pink bell-shaped flowers and makes a charming addition to a rock garden. It is easily propagated by cuttings or layering but is listed as a “sensitive” species in Washington, so any wild collecting should be undertaken judiciously. Black Crowberry, Empetrum nigrum, is not an ericad but is in a related family, empetraceae. It has black berries, sometimes eaten by natives, but a favorite of bears. This low, creeping, mat-forming shrub is easily propagated by cuttings.