Saskatoon Serviceberry The Rose Family–Rosaceae

Amelanchier alnifolia (Nutt.) Nut. ex M. Roem

(am-el-ang-KEY-er aln-IH-foal-ee-uh)

Names: Saskatoon Serviceberry is a combination of two of its most familiar common names. It is also known as Juneberry, or Western Serviceberry. Historically it was also called “pigeon berry.” In some regions, serviceberry is pronounced “sarvis”-berry. Saskatoon comes from the Cree word for Serviceberry. The city of Saskatoon, Saskatchewan was named after the berry. The name “serviceberry” apparently comes from the similarity of the fruit to the related European Sorbus. The origin of the generic name Amelanchier is derived from the French name of the European species, Amelanchier ovalis. Alnifolia means “alder-like” leaves.

Relationships: There are about 20 species of Amelanchier, all shrubs or small trees. Most are native to North America with two in Asia and one in Europe. In some literature, Saskatoon Serviceberry is listed as Amelanchier florida. Notable varieties in the west include var. semiintegrifolia (Douglas, quoted in Hitchcock & Cronquist, writes that it is “plentiful about the Grand Rapids, and at Fort Vancouver, on the Columbia, and on the high ground of the Multnomak (sic) River.;” var. cusickii from the east side of the Cascades has larger flowers; and var. humptulipensis was discovered on the Humptulips Prairie in Grays Harbor County, Washington. Serviceberries hybridize readily making species identification sometimes difficult. Cultivated varieties are grown for larger, sweeter berries, especially in Alberta, Saskatchewan, and Manitoba.

Relationships: There are about 20 species of Amelanchier, all shrubs or small trees. Most are native to North America with two in Asia and one in Europe. In some literature, Saskatoon Serviceberry is listed as Amelanchier florida. Notable varieties in the west include var. semiintegrifolia (Douglas, quoted in Hitchcock & Cronquist, writes that it is “plentiful about the Grand Rapids, and at Fort Vancouver, on the Columbia, and on the high ground of the Multnomak (sic) River.;” var. cusickii from the east side of the Cascades has larger flowers; and var. humptulipensis was discovered on the Humptulips Prairie in Grays Harbor County, Washington. Serviceberries hybridize readily making species identification sometimes difficult. Cultivated varieties are grown for larger, sweeter berries, especially in Alberta, Saskatchewan, and Manitoba.

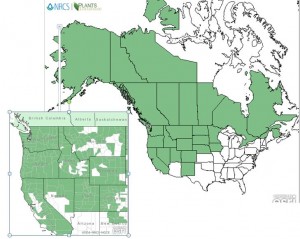

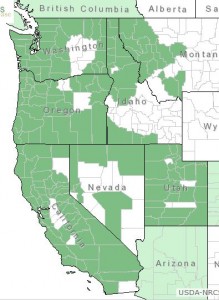

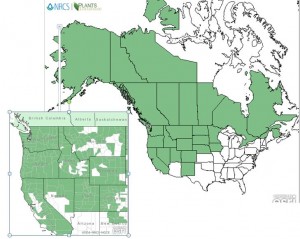

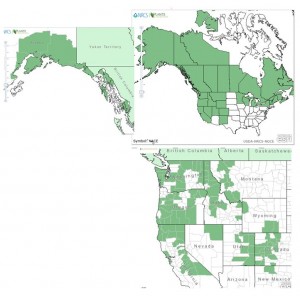

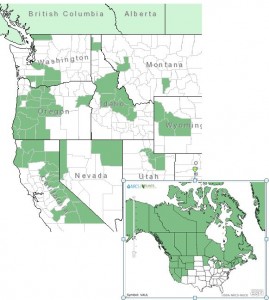

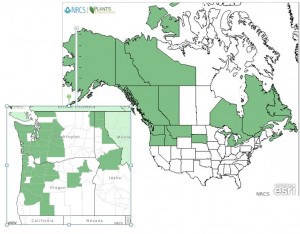

Distribution of Saskatoon Serviceberry from USDA Plants Database

Distribution: Saskatoon Serviceberry is found throughout most of Canada and western North America; from Alaska to California in the west; reaching eastward in Canada to Quebec; to western Colorado and northern Nebraska and Iowa in the United States.

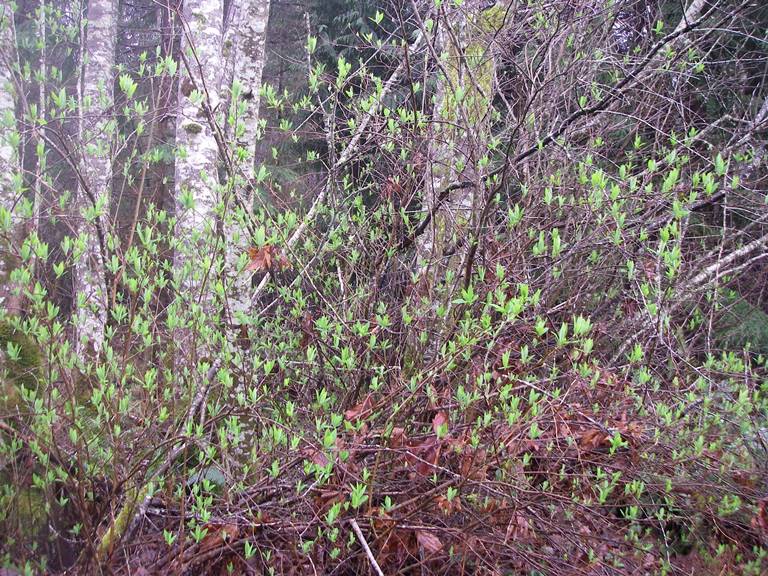

Growth: Saskatoon Serviceberry grows 3-15 ft. (1-5m) tall, sometimes taller. It is relatively short-lived; most will live about 20 years but some have survived to 85.

Growth: Saskatoon Serviceberry grows 3-15 ft. (1-5m) tall, sometimes taller. It is relatively short-lived; most will live about 20 years but some have survived to 85.

Habitat: It grows in a variety of habitats from rocky shorelines, stream banks, and open forests to prairies and dry mountain slopes. Wetland designation: FACU, It usually occurs in non-wetlands, but occasionally is found on wetlands.

Diagnostic Characters: The thin, round leaves of Saskatoon Serviceberry are entire (not toothed) at the base and regularly toothed along the upper margin. The showy flowers are white and star-like. The ripe fruit is a small berry-like pome; dark, reddish purple to nearly black.

In the Landscape: Serviceberry is an outstanding landscape plant. Not only is it attractive through every season, it has the bonus of producing edible fruit. In spring, it is loaded with bright, star-like white blossoms. In late summer, it produces clusters of purplish-black little “apples;” soon followed by the changing of the leaves to yellow or red in autumn. An attractive branching pattern adds winter interest. It grows in sun or partial shade; and is superb in an open woodland garden or on a sunny bank.

Phenology: Bloom time: May-June. Fruit ripens: July-August.

Propagation: Seeds require a cold stratification for 180 days at 40ºF (4ºC). “Green” seeds that are harvested before they are fully formed and the seed coat has hardened may require less time. Stored seed may benefit from a warm stratification period for 4 weeks prior to the cold stratification; otherwise seeds may take 18 months or more to germinate. Suckers that have roots may be divided from the mother plant. Layering is possible but it may take 18 months for roots to grow sufficiently.

Use by People: Natives ate the fruit fresh and dried; some used it to season soup or meat. Some tribes used burning to encourage stands of Saskatoon; it will resprout from the root crown or rhizomes after the top is killed by fire and may fruit again after two years. Interior tribes used the tough wood for arrows, digging sticks, and drying racks. Coastal tribes used it for rigging their halibut lines. The Snohomish used the wood to make discs for a gambling game called slahalem. In early American folklore, the plant’s flowering time signaled pioneers that the ground had thawed enough in spring for the burial of the winter’s dead. Today people use the fruit for making pastries, jellies and syrups.

Use by People: Natives ate the fruit fresh and dried; some used it to season soup or meat. Some tribes used burning to encourage stands of Saskatoon; it will resprout from the root crown or rhizomes after the top is killed by fire and may fruit again after two years. Interior tribes used the tough wood for arrows, digging sticks, and drying racks. Coastal tribes used it for rigging their halibut lines. The Snohomish used the wood to make discs for a gambling game called slahalem. In early American folklore, the plant’s flowering time signaled pioneers that the ground had thawed enough in spring for the burial of the winter’s dead. Today people use the fruit for making pastries, jellies and syrups.

Use by Wildlife: Saskatoon serviceberry is a valuable wildlife plant. Many species of rodents and songbirds eat the fruits, including chipmunks, crows, thrushes, robins and Western Tanagers. Black Bears, beaver, marmots, and hares eat twigs, foliage, fruits and bark. Moose elk, and deer, especially Mule Deer, browse the twigs and foliage; however due to the high concentration of cyanogenic glycosides in young twigs, a diet consisting of more than 35% Saskatoon Serviceberry may be fatal.

Links:

USDA Plants Database

Consortium of Pacific Northwest Herbaria

WTU Herbarium Image Collection, Plants of Washington, Burke Museum

E-Flora BC, Electronic Atlas of the Flora of British Columbia

Jepson Eflora, University of California

Calphotos

Ladybird Johnson Wildflower Center

USDA Forest Service-Fire Effects Information System

Virginia Tech ID Fact Sheet

Native Plants Network, Propagation Protocol Database

Plants for a Future Database

Native American Ethnobotany, University of Michigan, Dearborn

Dwarf Serviceberry

Amelanchier pumila (Torr. & A. Gray) Nutt. ex M. Roem.

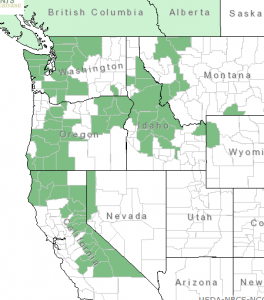

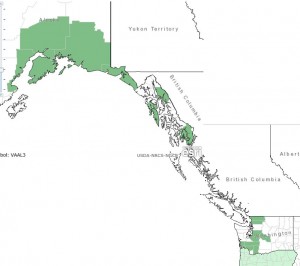

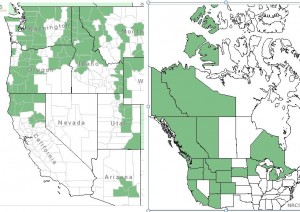

This species is often listed as a variety of Saskatoon Serviceberry (A. alnifolia var. pumila) and is very similar except for its smaller stature (pumila means dwarf) and smoother, less fuzzy flowers and leaves. It grows 3-6 feet (1-2m) tall. Its leaves are somewhat leathery. In Washington, it is more common on the eastern slopes of the Cascades; its range extending through the Sierras of California, eastward to western Montana and northwestern New Mexico. Dwarf Serviceberry is at home on drier mountain slopes and open prairies.

Links:

USDA Plants Database

Consortium of Pacific Northwest Herbaria

Jepson Eflora, University of California

Calphotos

Names: The word Spiraea comes from a Greek plant that was commonly used for garlands. This species is also known as Spiraea densiflora. Splendens means shiny, densiflora means dense flowers. Subalpine Spiraea is also known as Rosy Spirea, or Rose or Mountain Meadowsweet.

Names: The word Spiraea comes from a Greek plant that was commonly used for garlands. This species is also known as Spiraea densiflora. Splendens means shiny, densiflora means dense flowers. Subalpine Spiraea is also known as Rosy Spirea, or Rose or Mountain Meadowsweet.

Spiraea lucida Douglas ex Greene

Spiraea lucida Douglas ex Greene

Growth: Shinyleaf Spiraea grows only to about 1-3 ft. (30-90 cm). It spreads by rhizomes and often grows in large colonies.

Growth: Shinyleaf Spiraea grows only to about 1-3 ft. (30-90 cm). It spreads by rhizomes and often grows in large colonies.

Pyramidal Spiraea, Spiraea x pyramidata, is a naturally occurring hybrid of S. betulifolia (lucida) and S. douglasii. It is intermediate to both of its parents, growing 4-5 feet (130-160cm) with flowers in pyramidal clusters, white to pale pink.

Pyramidal Spiraea, Spiraea x pyramidata, is a naturally occurring hybrid of S. betulifolia (lucida) and S. douglasii. It is intermediate to both of its parents, growing 4-5 feet (130-160cm) with flowers in pyramidal clusters, white to pale pink.

Names: The word Spiraea comes from a Greek plant that was commonly used for garlands. Douglas Spiraea is named after David Douglas. It is also commonly known as Hardhack, Steeplebush, or as Western, Pink or Rose Spiraea. There are two recognized varieties, var. douglasii, which has grayish wooly hairs on the undersides of its leaves; and var. menziesii, (sometimes known as S. menziesii) which has smooth or only slightly hairy leaves.

Names: The word Spiraea comes from a Greek plant that was commonly used for garlands. Douglas Spiraea is named after David Douglas. It is also commonly known as Hardhack, Steeplebush, or as Western, Pink or Rose Spiraea. There are two recognized varieties, var. douglasii, which has grayish wooly hairs on the undersides of its leaves; and var. menziesii, (sometimes known as S. menziesii) which has smooth or only slightly hairy leaves.

Habitat: Douglas Spiraea grows in open areas of wet meadows, bogs, streambanks, and lake margins. Labrador Tea, Ledum groenlandicum, is often a companion of Douglas Spiraea in bogs. It can withstand drier periods in areas that are only seasonally wet. Wetland designation: FACW, It usually occurs in wetlands, but is occasionally found in non-wetlands.

Habitat: Douglas Spiraea grows in open areas of wet meadows, bogs, streambanks, and lake margins. Labrador Tea, Ledum groenlandicum, is often a companion of Douglas Spiraea in bogs. It can withstand drier periods in areas that are only seasonally wet. Wetland designation: FACW, It usually occurs in wetlands, but is occasionally found in non-wetlands. In landscapes: Douglas Spiraea is especially useful in Rain Gardens, but care should be taken not to introduce it to an area where it is likely to overtake other desirable plants. It is a good choice for revegetation projects along streamsides. Its attractive purplish-pink flower plumes create a “sea of pink” in “Hardhack bogs” when in bloom.

In landscapes: Douglas Spiraea is especially useful in Rain Gardens, but care should be taken not to introduce it to an area where it is likely to overtake other desirable plants. It is a good choice for revegetation projects along streamsides. Its attractive purplish-pink flower plumes create a “sea of pink” in “Hardhack bogs” when in bloom.

Names: Physo means bladder, carpus means fruit, referring to the inflated fruits. Capitatus means having a head, referring to its dense flower or fruit cluster. Ninebarks are so called because it was believed there are nine layers (or nine strips) of peeling bark on the stems. In the past it has been lumped in with P. opulifolia, Common Ninebark (an eastern species); along with this species, it was also known as Opulaster capitatus and Neillia opulifolia, Opulaster and opulifolia mean rich in flowers (asters) or in leaves (folia)–they may also refer to its similarity to Viburnum opulus. Because of its close association to spiraeas, it has also been known as Spiraea capitata. Western Ninebark is another common name.

Names: Physo means bladder, carpus means fruit, referring to the inflated fruits. Capitatus means having a head, referring to its dense flower or fruit cluster. Ninebarks are so called because it was believed there are nine layers (or nine strips) of peeling bark on the stems. In the past it has been lumped in with P. opulifolia, Common Ninebark (an eastern species); along with this species, it was also known as Opulaster capitatus and Neillia opulifolia, Opulaster and opulifolia mean rich in flowers (asters) or in leaves (folia)–they may also refer to its similarity to Viburnum opulus. Because of its close association to spiraeas, it has also been known as Spiraea capitata. Western Ninebark is another common name.

Propagation: Pacific Ninebark is easy to start from cuttings, or live stakes (direct planting of a cutting into its desired location). Seed propagation is possible, but much slower. Fall is the best time to sow the seeds, although many sources state that it does not require a stratification period.

Propagation: Pacific Ninebark is easy to start from cuttings, or live stakes (direct planting of a cutting into its desired location). Seed propagation is possible, but much slower. Fall is the best time to sow the seeds, although many sources state that it does not require a stratification period.

Diagnostic Characters: Its leaves are bright green in spring, lance-shaped, and entire (not toothed); and smell like cucumber when crushed. Small, five-lobed flowers are born in drooping clusters, usually appearing before the leaves. Each flower is white with a green calyx. They are said to have an unusual fragrance

Diagnostic Characters: Its leaves are bright green in spring, lance-shaped, and entire (not toothed); and smell like cucumber when crushed. Small, five-lobed flowers are born in drooping clusters, usually appearing before the leaves. Each flower is white with a green calyx. They are said to have an unusual fragrance  “something between watermelon rind and cat urine.” Others compare it to almonds. Some sources report that the female flowers have a pleasant fragrance, but the male flowers are unpleasant. The fruit are like small plums. Immature fruit is peach-colored, mature fruit is purple or bluish-black. Since Indian Plum is dioecious, you need to a have a female plant with nearby males for it to bear fruit. In natural populations, there are usually more males than females, due to a higher mortality of females. Males often flower at an earlier age than females; females have a slower growth rate.

“something between watermelon rind and cat urine.” Others compare it to almonds. Some sources report that the female flowers have a pleasant fragrance, but the male flowers are unpleasant. The fruit are like small plums. Immature fruit is peach-colored, mature fruit is purple or bluish-black. Since Indian Plum is dioecious, you need to a have a female plant with nearby males for it to bear fruit. In natural populations, there are usually more males than females, due to a higher mortality of females. Males often flower at an earlier age than females; females have a slower growth rate.

Holodiscus discolor (Pursh.) Maxim

Holodiscus discolor (Pursh.) Maxim

Diagnostic Characters: Oceanspray can be recognized by its alternate, oval to triangular leaves with lobed or coarsely and doubly toothed margins. The green, upper surface of the leaves can be smooth or coarsely-hairy; the paler, under surface is strongly veined and soft-hairy. Its flowers are white to cream with lilac-like drooping clusters. Seeds are actually wooly achenes (dry, one-seeded fruit) in tiny dry capsules. It usually has several main stems with brownish peeling bark; the ends of the branches arch gracefully outward.

Diagnostic Characters: Oceanspray can be recognized by its alternate, oval to triangular leaves with lobed or coarsely and doubly toothed margins. The green, upper surface of the leaves can be smooth or coarsely-hairy; the paler, under surface is strongly veined and soft-hairy. Its flowers are white to cream with lilac-like drooping clusters. Seeds are actually wooly achenes (dry, one-seeded fruit) in tiny dry capsules. It usually has several main stems with brownish peeling bark; the ends of the branches arch gracefully outward.

Phenology: Bloom time: June-July. Fruit ripens: Late summer.

Phenology: Bloom time: June-July. Fruit ripens: Late summer.

Relationships: There are about 20 species of Amelanchier, all shrubs or small trees. Most are native to North America with two in Asia and one in Europe. In some literature, Saskatoon Serviceberry is listed as Amelanchier florida. Notable varieties in the west include var. semiintegrifolia (Douglas, quoted in Hitchcock & Cronquist, writes that it is “plentiful about the Grand Rapids, and at Fort Vancouver, on the Columbia, and on the high ground of the Multnomak (sic) River.;” var. cusickii from the east side of the Cascades has larger flowers; and var. humptulipensis was discovered on the Humptulips Prairie in Grays Harbor County, Washington. Serviceberries hybridize readily making species identification sometimes difficult. Cultivated varieties are grown for larger, sweeter berries, especially in Alberta, Saskatchewan, and Manitoba.

Relationships: There are about 20 species of Amelanchier, all shrubs or small trees. Most are native to North America with two in Asia and one in Europe. In some literature, Saskatoon Serviceberry is listed as Amelanchier florida. Notable varieties in the west include var. semiintegrifolia (Douglas, quoted in Hitchcock & Cronquist, writes that it is “plentiful about the Grand Rapids, and at Fort Vancouver, on the Columbia, and on the high ground of the Multnomak (sic) River.;” var. cusickii from the east side of the Cascades has larger flowers; and var. humptulipensis was discovered on the Humptulips Prairie in Grays Harbor County, Washington. Serviceberries hybridize readily making species identification sometimes difficult. Cultivated varieties are grown for larger, sweeter berries, especially in Alberta, Saskatchewan, and Manitoba.

Growth: Saskatoon Serviceberry grows 3-15 ft. (1-5m) tall, sometimes taller. It is relatively short-lived; most will live about 20 years but some have survived to 85.

Growth: Saskatoon Serviceberry grows 3-15 ft. (1-5m) tall, sometimes taller. It is relatively short-lived; most will live about 20 years but some have survived to 85.

Use by People: Natives ate the fruit fresh and dried; some used it to season soup or meat. Some tribes used burning to encourage stands of Saskatoon; it will resprout from the root crown or rhizomes after the top is killed by fire and may fruit again after two years. Interior tribes used the tough wood for arrows, digging sticks, and drying racks. Coastal tribes used it for rigging their halibut lines. The Snohomish used the wood to make discs for a gambling game called slahalem. In early American folklore, the plant’s flowering time signaled pioneers that the ground had thawed enough in spring for the burial of the winter’s dead. Today people use the fruit for making pastries, jellies and syrups.

Use by People: Natives ate the fruit fresh and dried; some used it to season soup or meat. Some tribes used burning to encourage stands of Saskatoon; it will resprout from the root crown or rhizomes after the top is killed by fire and may fruit again after two years. Interior tribes used the tough wood for arrows, digging sticks, and drying racks. Coastal tribes used it for rigging their halibut lines. The Snohomish used the wood to make discs for a gambling game called slahalem. In early American folklore, the plant’s flowering time signaled pioneers that the ground had thawed enough in spring for the burial of the winter’s dead. Today people use the fruit for making pastries, jellies and syrups.

Growth: Oval-leaved Blueberry grows from 3-9ft. (1-3m), and grows a maximum of 12 inches (30cm) a year.

Growth: Oval-leaved Blueberry grows from 3-9ft. (1-3m), and grows a maximum of 12 inches (30cm) a year. Diagnostic Characters: The young twigs of Oval-leaved Blueberry are brownish or reddish to yellowish, angled and grooved. Flowers are urn-shaped and pink; they usually appear before or with the oval-shaped leaves. Berries are blue-black with a bluish bloom—very much like commercial blueberries.

Diagnostic Characters: The young twigs of Oval-leaved Blueberry are brownish or reddish to yellowish, angled and grooved. Flowers are urn-shaped and pink; they usually appear before or with the oval-shaped leaves. Berries are blue-black with a bluish bloom—very much like commercial blueberries.

Names: Mountain Huckleberry is also known as Thin-leaf Huckleberry (membranaceum = thin, like a membrane). It is also known as Big, Black, or Blue Huckleberry. It is Idaho’s State Fruit.

Names: Mountain Huckleberry is also known as Thin-leaf Huckleberry (membranaceum = thin, like a membrane). It is also known as Big, Black, or Blue Huckleberry. It is Idaho’s State Fruit.

.

. Diagnostic Characters: Mountain Huckleberry has thin leaves with finely toothed margins that are pointed at the tip. Flowers are urn-shaped and creamy-pink. The berries are purplish or reddish-black, without a waxy bloom.

Diagnostic Characters: Mountain Huckleberry has thin leaves with finely toothed margins that are pointed at the tip. Flowers are urn-shaped and creamy-pink. The berries are purplish or reddish-black, without a waxy bloom.